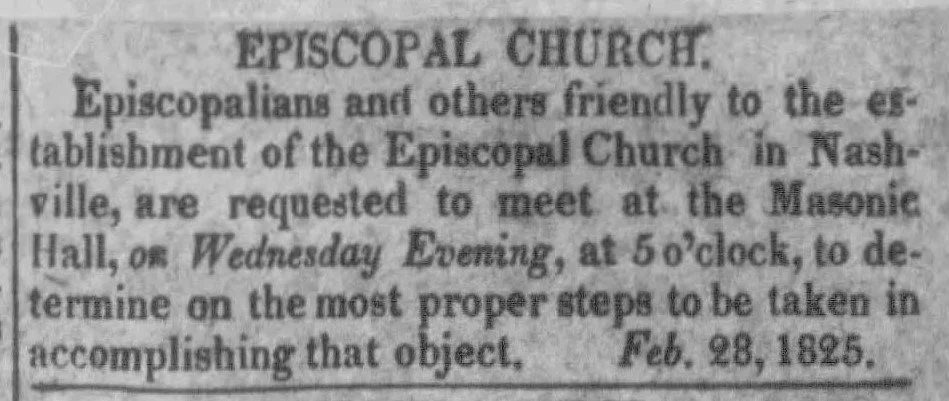

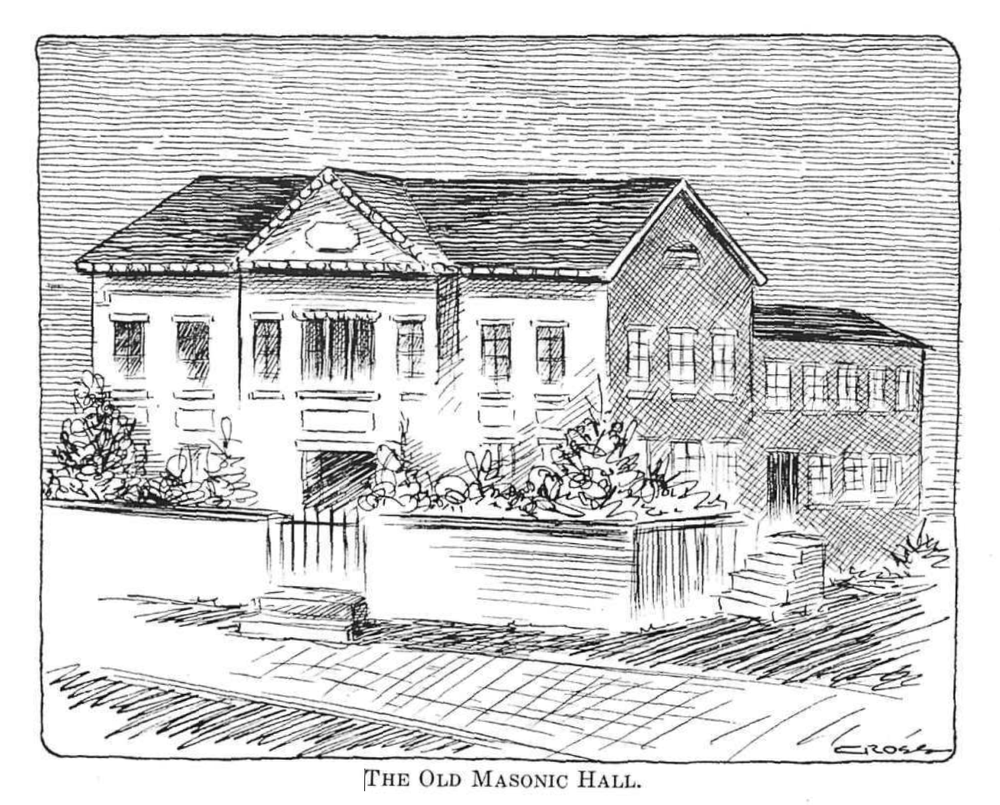

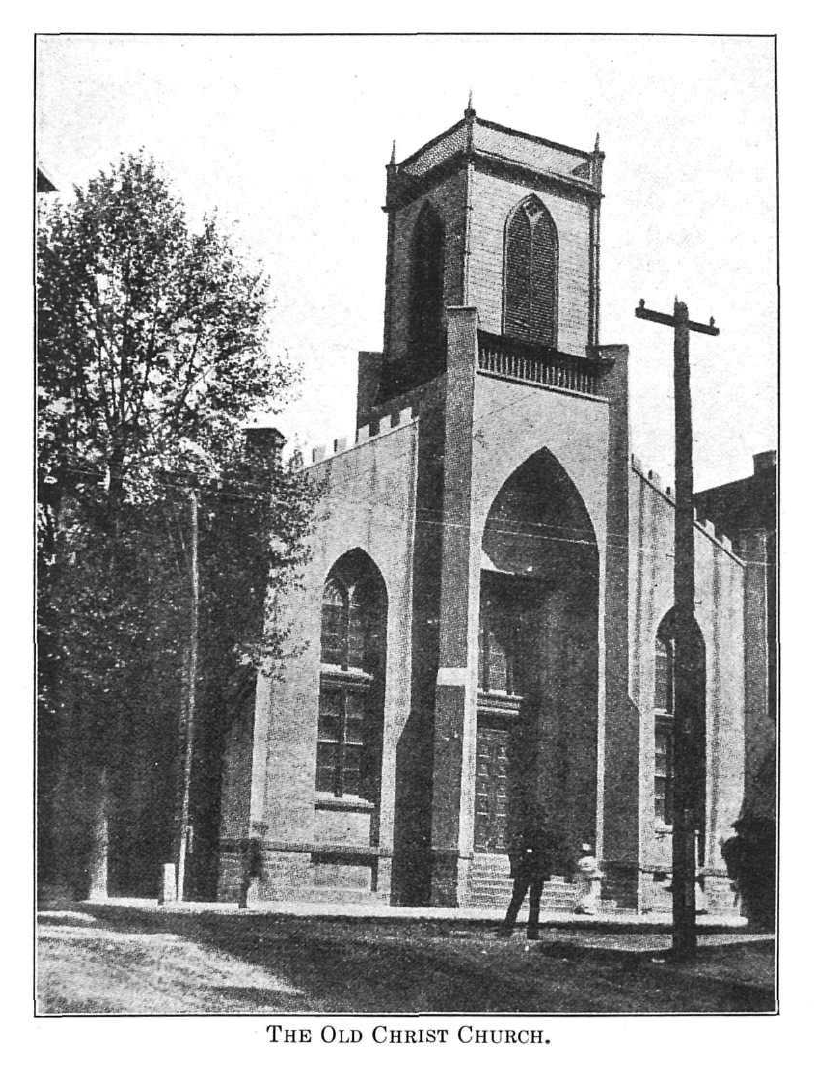

The beginning of Christ Church is traditionally dated to 1829, although in reality the organization of the parish took several years. It all began in 1825 with gatherings of about two dozen Episcopalians for worship that was led by a series of visiting Episcopal clergy. Over the next few years, the community typically met in the basement of Nashville’s Masonic Hall, although sometimes they worshipped in the local Baptist, Methodist, or Presbyterian churches. Rev. James Hervey Otey, future Bishop of Tennessee, performed the first baptism of the parish in 1826. The first Vestry was elected in 1828 and plans were soon drawn up for an Episcopal church in Nashville. The Vestry purchased land for the church building in 1829 at the corner of Spring and High Streets (now Church Street and Sixth Avenue), and the cornerstone was laid in an elaborate ceremony in July 1830. The year 1831 saw the completion of the church building and sale of church pews by auction. The first Christ Church would serve the congregation for more than six decades, until the erection of the present church structure in the 1890s.

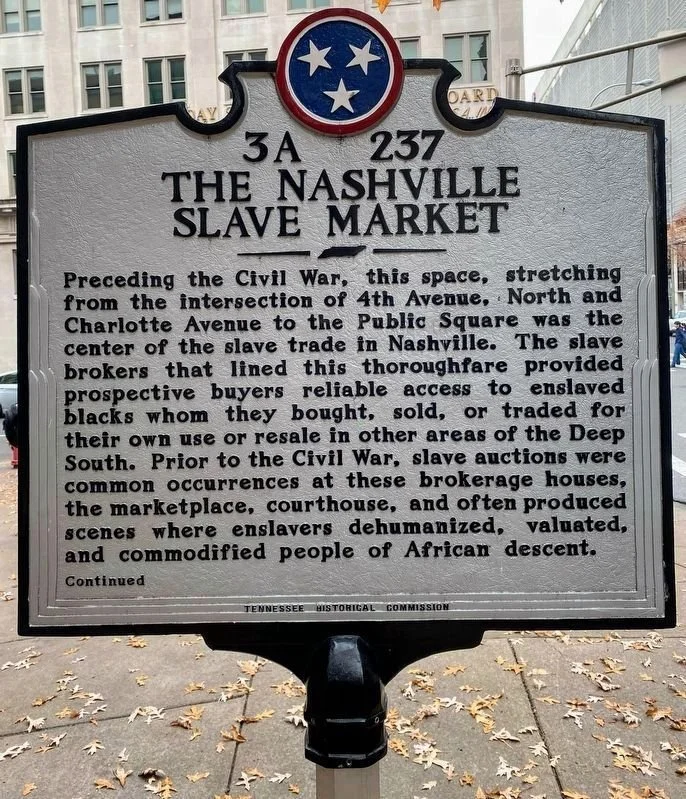

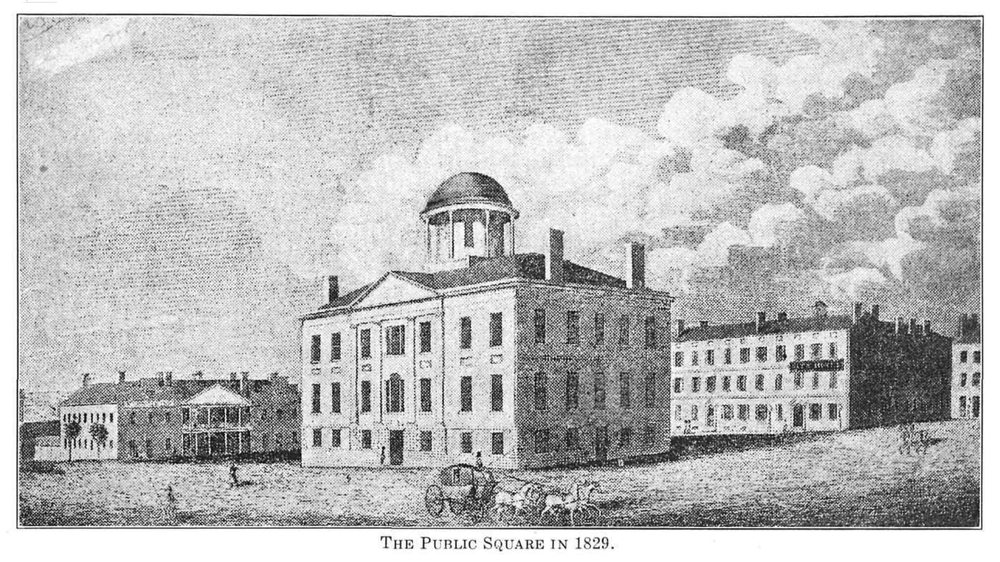

At the time the church was founded, Nashville, Davidson County, and the region of Middle Tennessee more generally was a center of slave ownership. The 1830 U.S. Census recorded a population of 28,122 persons in Davidson County, of whom 58.5 percent were free and 41.5 percent were enslaved. This was the largest number of slaves in any county of Tennessee, and the highest percentage of any Tennessee county’s population to be enslaved. Counties adjacent to Davidson County also tended to have unusually large enslaved populations. All this was due in part to Nashville’s river port and relative proximity to Memphis and the Mississippi River. “Slave Auctions,” as they were called, were regularly held at Public Square, just three blocks from the site of the original Christ Church building. Local newspapers frequently advertised auctions as well as individual sales and rental of slaves. In other words, the sale and trafficking of enslaved persons was big business in Nashville.

The small community of Episcopalians who founded Christ Church were part of the social and economic elite of Nashville, and most of them owned slaves. A small but significant minority of early Christ Church members owned large farms or plantations with dozens or, rarely, hundreds of slaves. They could accumulate great fortunes by exploiting unfree labor. The founding members active between 1825 and 1831 included Henry Middleton Rutledge, son of a signer of the Declaration of Independence, whose lands and properties in Tennessee were maintained by a force of 60 slaves in 1820 and 57 slaves in 1830. Another major slaveowner was Col. Andrew Hynes, veteran of the War of 1812 and proprietor of the mercantile firm Andrew Hynes & Co., who owned 45 slaves in 1830 and 48 slaves in 1840. Others might manage a smaller farm or enterprise with perhaps ten to twenty slaves. However, the male heads of household of the majority of slaveholding families at Christ Church were lawyers, doctors, merchants, teachers, and other professionals who lived in town. They tended to enslave a smaller number of persons, usually no more than ten, who labored as domestic servants, cooks, maids, nurses, valets, coachmen, etc. For all slaveowners, the possession of slaves provided clear economic advantage but also served as a symbol of status and achievement, and it signified membership in the nation’s elite.

Isaac Project research has demonstrated the degree to which the early Christ Church parish was a slaveowners’ church. All seven men who served as rectors to Christ Church in the years before 1865, for instance, were slaveholders at some point in their lives. Whether we look at founding members of the parish in the 1820s, early donors to the church, or members of the clergy and Vestry during the years of slavery, we find that at least 85 percent were slaveholders at some point during their association with Christ Church. The percentage may be higher, since with some individual families we have not yet been able to determine whether they owned slaves.

Yet even the wealthy founders of the church needed to do some serious fundraising to pay for the construction of the new church and the hiring of a pastor. The community pursued two main strategies, each of which tells us something about the nature of Nashville’s racial, social, and class hierarchies at the time.

One strategy was pew rent, often described in early sources as the “sale” or “auction” of pews. Paying to rent a pew is a foreign concept for modern church goers, but it was common practice in the 1800s. Pew rentals served as a source of income that helped reduce a church’s debts. Early pews were often box pews and not bench pews, so boxes were “let” or rented on an annual basis. In Nashville, Downtown Presbyterian Church, St. Patrick Catholic Church, and Christ Church, among others, all rented pews that designated a specific location for the exclusive use of paying parishioners and their families. At Christ Church, pew rental began in 1831 with the completion of the first building. Fifty-two prominent Nashvillians paid pew rent at the new church. At least forty-six of these individuals (89 percent) were slaveowners at some point during their lives. Pew rental created inequalities that disadvantaged not only the enslaved but also non-slave-owning white communicants. Socially and economically advantaged members were granted prime spots for worship, while those without wealth were relegated to limited free spots for the public. It was the pew renters who tended to dominate positions on the Vestry and in church offices such as Senior and Junior Warden. Thus was economic privilege converted to dominant control of the church as an institution.

The second fundraising tactic was an annual bazaar put on by members of Christ Church’s Parish Aid and Sewing Society. This organization was founded in 1829 by the female members of the prominent early Christ Church families. Its first treasurer was Mary A. Washington (1803-1867), a long-time church communicant together with her husband Thomas Washington. The parish aid society has been credited with raising the funds that paid for the purchase of land for the first Christ Church building ($2,400) and with helping to pay off the debt on the structure itself, which had cost $16,000. The chief source of income at the annual church bazaar, according to the official church history published in 1929, was the “tempting dishes made from famous recipes of those fine old housekeepers.” Fundraising dinners are nothing unique to Christ Church, but it must be noted that the fine old housekeepers who put on such events in the early days of the parish most likely had the assistance of their enslaved domestic servants and cooks. Whether they labored in a field or served in a kitchen, enslaved persons made a direct contribution to the building, funding, and maintenance Christ Church.

Sources and further reading:

Abstract of the Returns of the 1830 Census, Washington, D. C., 1832

“First Presbyterian Church of Nashville History,” https://fpcnashville.org/home/history/

“The Nashville Slave Market,” The Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=145783

Rankin, Anne, ed. Christ Church Nashville, 1829-1929. Nashville: Marshall & Bruce, 1929.

“St. Patrick Catholic Church: Our History,” https://stpatricksnashville.org/our-history

1820 U.S. Federal Census, record for Henry M. Rutlidge, Franklin County, Tennessee

1830 U.S. Federal Census, record for Andrew Hynes, Davidson County, Tennessee

1830 U.S. Federal Census, record for H. M. Rutlidge, Franklin County, Tennessee

1840 U.S. Federal Census, record for Andrew Hynes, Davidson County, Tennessee

Historical marker in downtown Nashville marking the site of the Nashville slave market, erected in 2018. Source: The Historical Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=145783

First newspaper announcement of an Episcopal gathering in Nashville. Source: Nashville Whig, Monday, February 28, 1825

The Public Square in Nashville, site of slave auctions, as it looked in 1829. Source: Anne Rankin, ed., Christ Church Nashville, 1829-1929, Nashville: Marshall & Bruce, 1929, facing p. 33.

The former Masonic Hall, where Nashville Episcopalians worshiped in the 1820s.. Source: Anne Rankin, ed., Christ Church Nashville, 1829-1929, Nashville: Marshall & Bruce, 1929, facing p. 44.

The first Christ Church sanctuary, constructed in 1830-31. Source: Anne Rankin, ed., Christ Church Nashville, 1829-1929, Nashville: Marshall & Bruce, 1929, facing p. 65.