In the summer of 1967, St. Anselm’s Episcopal Chapel and Student Center (now St. Anselm’s Episcopal Church) operated a summer education program for children in North Nashville. The “liberation school,” as it became known, was rooted in earlier efforts to make early childhood education central to the civil rights movement. It aimed to augment the education of Black children in the city’s public schools, which had only been nominally integrated a decade after the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Across a wide-ranging curriculum that covered math, science, humanities, and civics, Black students were taught that they themselves, their communities, culture, and history had inherent value, despite the racist attitudes and structures that continued to dominate their lives. That uplifting program became the subject of controversy when a Nashville police captain testified before the U.S. Senate that the school was using federal funds to teach Black children to “hate whitey.” Unpacking this brief episode during the “long, hot summer” of 1967 reveals much about race relations in late-1960s Nashville, the evolving state of the civil rights movement, and Christ Church’s response to protests for and against racial equity.

St. Anselm’s began in the mid-1950s as an outreach ministry of the Church of the Holy Trinity, a historically African-American parish. The chapel would serve students at North Nashville’s three historically Black institutions of higher education—Fisk University, Meharry Medical College, and Tennessee Agricultural & Industrial State College (now Tennessee State University). Holy Trinity parishioner and prominent local civil-rights leader Z. Alexander Looby donated land on Meharry Boulevard for the chapel and student center. It was built in 1960 with funds from the Episcopal Development Council (EDC), a coalition of Nashville-area Episcopal churches in which Christ Church and its members played leading roles. Looby and his family lived at St. Anselm’s after his nearby house was bombed in April 1960, at the height of student-led lunch counter sit-ins downtown. Rev. James E. P. Woodruff, a committed civil rights activist, was called as St. Anselm’s first chaplain and campus minister in 1961.

A few years prior, the EDC had funded another chapel, St. Augustine’s, to serve Nashville’s predominantly white institutions—Vanderbilt University, Peabody College for Teachers (now part of Vanderbilt), and Ward-Belmont College (now Belmont University). Christ Church contributed to the establishment of both St. Anselm’s and St. Augustine’s. But the vestry expressed greater interest in and an ongoing commitment to St. Augustine’s. It appointed a delegate to the chapel’s College Work Committee in January 1961 and commended its chaplain in May 1963 for his “fine work.”

By contrast, St. Anselm’s appears only briefly and incidentally in minutes of the vestry’s meetings during this time. In November 1961, the vestry discussed donating an unused baptismal font to the chapel (subsequently approved) and invited Rev. Woodruff—along with Rev. James E. Williams, rector of Holy Trinity—to participate in weekday services during Lent. The only other mention of St. Anselm’s prior to the “liberation school” controversy concerns a December 1964 request by the Episcopal Society for Cultural and Racial Unity (ESCRU) to meet at Christ Church. ESCRU was founded in 1959 as a coalition of clergy and laity that used tactics of civil disobedience and nonviolent protest drawn from the civil rights movement to work against racism within the Episcopal Church. The Nashville chapter met at St. Anselm’s but wanted to encourage more participation across the diocese from historically white parishes. In their discussion of ESCRU’s request, the Christ Church vestry described the biracial initiative as “a militant controversial group.” Because the meeting adjourned without resolving the question and the vestry never returned to the matter in subsequent meetings, they presumably did not permit ESCRU to use the church.

The liberation school—officially, the North Nashville Student Summer Project— operated at St. Anselm’s from mid-June to mid-August 1967. However it originated several months prior through the efforts of Fisk University students interested in working with disadvantaged children in North Nashville. The group was led by Stanley Alprin, chair of the elementary education department. Most of those who volunteered to teach were members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced and often printed as “Snick”), a student-led civil rights organization that emerged from the lunch counter sit-ins of the early 1960s. Its curriculum was inspired by the earlier Freedom Schools, a network of SNCC-sponsored educational programs that flourished in the Mississippi Delta during the Freedom Summer of 1964.

The Freedom Schools were designed to augment the curriculum of the South’s still racially segregated schools. They combined academics—math and science but especially civics, history, and African-American literature—with community-based extracurricular activities, and met in church basements, unused storefronts, and community members’ homes. By emphasizing a culture of learning and by centering the unique perspectives, experiences, and contributions of Black individuals and communities, the Freedom Schools positioned “the student as a force for social change.”

Originally, ninety percent of the Freedom Schools’ teachers were northern white volunteers. This created intense internal deliberations among SNCC organizers. Prominent members like John Lewis and Fanny Lou Hamer argued that this was an effective way of modeling the integrated society the civil rights movement hoped to achieve. In a more practical sense, others argued that privileged white northerners would bring greater publicity to the cause while also being less likely to be met with violence than Black educators. Still, others argued, to the contrary, that this limited opportunities for cultivating Black leaders and risked reinforcing stereotypes about African Americans’ need for white guidance and support to achieve their goals.

By the late 1960s, the Freedom Schools had largely disappeared, though they provided a model for later efforts like the Liberation Schools sponsored by the Black Panther Party. (Founded on the West Coast in 1969, the Black Panthers’ schools were not connected to the Nashville program.) During the same years, SNCC became more closely aligned with the Black Power movement. This meant its earlier reliance on interracial cooperation within the civil rights movement was replaced with an emphasis on Black self-determination and autonomy. Unlike the earlier Freedom Schools, all the teachers in Nashville’s liberation school were Black, and the curriculum openly embraced the politics of Black Power. Willful misunderstanding and fearmongering by whites about the meaning of Black Power would overshadow the later years of the civil rights movement and the St. Anselm’s liberation school specifically.

Prior to its affiliation with St. Anselm’s, the liberation school met at a community center on Jefferson Street operated by the Metropolitan Action Committee (MAC), a mayoral commission that was tasked with the local administration and distribution of federal anti-poverty funds. Mayor Beverly Briley appointed J. Paschall Davis, an attorney and member of the Christ Church vestry from 1951 through 1957 who was ordained to the priesthood in 1961, as chairman of MAC shortly after its creation in 1965. From the beginning, MAC was plagued with mismanagement, inefficiencies, and paternalistic attitudes toward both its employees and the recipients of its aid. When asked about discrimination alleged by MAC’s Black employees, for example, Davis all but confirmed the accusations, claiming “the child can’t give directions to the parents.” The liberation school met at MAC’s Jefferson Street location from February until May 1967, when the Committee shuttered all its community centers. Reporters for the Tennessean noted possible concerns about students in the liberation school being taught about Black Power, but MAC officials claimed the closures were simply part of an internal restructuring. Davis, for his part, claimed to have no knowledge the liberation school even existed.

In early June, as part of a wide-ranging invitation for youth-oriented proposals by MAC, Rev. Woodruff submitted a proposal that would rehabilitate the shuttered school, relocating it to St. Anselm’s and expanding its programming. Woodruff’s North Nashville Student Summer Project envisioned a broad emphasis on discrimination in housing, employment, municipal services, and other areas. It would include educational offerings for youth (the “liberation school” proper) and adults, a coffee house, a voter registration initiative, and a cooperative purchasing program. If this was born out of the immediate needs of North Nashvillians and made possible by an influx of antipoverty funds, it also fit squarely with Rev. Woodruff’s understanding of evangelism. As he stressed during an April 1966 service at St. Anselm’s, “The essence of Christian witness is to manifest the marks of Christ, his suffering, his poverty, and courage, to the fragmented and disintegrated persons of society.”

In July, MAC approved $7,770 to sponsor a program coordinator, nine student workers, and a share of the operating costs, although Woodruff had already begun work with private funds.

This work continued until early August when the liberation school and St. Anselm’s found itself at the center of a national controversy. This was entirely thanks to testimony by Capt. John Sorace, head of the Nashville Police Department’s intelligence division, before the Senate Judiciary Committee. The Committee was investigating the racial violence that plagued cities across the country during what the media dubbed the “long, hot summer” of 1967. Sorace had been called before the Committee to describe circumstances surrounding a days-long confrontation between police and North Nashvillians in April 1967.

Sorace, like the mainstream white media, blamed the unrest in Nashville on the inflammatory, militant rhetoric of Black Power. Specifically, he insinuated that SNCC—“an extremely dangerous organization, with people who hate, who teach hate”—was “actively contributing to the rioting in a variety of cities, certainly ours.” He implicated St. Anselm’s in this conspiracy by alleging that SNCC was using federal funds to involve “10-year-olds and 11-year-olds … in riot activities” through the liberation school. His claim that the liberation school was “teaching hatred for the white man” quickly gained national coverage.

It is worth noting that Sorace’s perspective was widely held among whites at the time, but it was not universal. The Kerner Commission, established by President Lyndon B. Johnson to investigate the root causes of that summer’s widespread violence, issued a report in 1968 that laid responsibility at the feet of “white America” for creating and maintaining “two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

In the aftermath of Sorace’s sensational testimony, Paschall Davis offered support for Woodruff and the liberation school, but misstatements and inaccuracies in his own testimony before the Judiciary Committee and the need for several rounds of corrections allowed Sorace’s claims to define the narrative. Within a week, the Rt. Rev. John Vander Horst, Bishop of Tennessee, issued a statement evicting the liberation school from St. Anselm’s, because “the curriculum of the school apparently deals with and teaches something quite contrary to our Christian heritage of reconciliation and love in the Lord.” The bishop also threatened disciplinary action against Woodruff. A few days later, MAC suspended the North Nashville Student Summer Project.

The controversy was also the subject of “considerable discussion” at the August 1967 meeting of the Christ Church vestry. Vestry member Cecil Wray, who also served as chair of MAC’s administration, personnel, and finance committee, delivered a “detailed, informative report,” and proposed a resolution commending the bishop’s actions against St. Anselm’s. The resolution passed unanimously.

The liberation school continued, at least for a time, meeting on Saturdays in nearby Watkins Park. Rev. Woodruff resigned his position at St. Anselm’s in mid-September, having lost the support of the bishop. Reflecting on criticisms of his activism, Woodruff insisted that anyone “interested in a better society” must “be able to hear and understand ‘unpopular’ ideas.” For him, this included an unwavering commitment to Black Power, which, he readily acknowledged, was in fact being taught at St. Anselm’s. What Nashville’s white civic and religious leaders, including those associated with Christ Church, failed (or refused) to understand was that Black Power, as Woodruff patiently clarified, was “not racial hatred. We’re teaching racial love, a love of the black people.”

Sources and Further Reading

The Minutes of the Vestry Meetings, 1961, 1963, and 1967, Christ Church Cathedral Archive, Nashville, Tennessee

Connie H. Choi, “Educate to Liberate: Black Panther Liberation Schools,” The Studio Museum of Harlem, https://www.studiomuseum.org/article/educate-liberate-black-panther-liberation-schools

Jon H. Hale, The Freedom Schools: Student Activists in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016)

Hearings before the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Ninetieth Congress, First Session, on H.R. 421 to Amend Title 18 of the United States Code to Prohibit Travel or Use of Any Facility in Interstate or Foreign Commerce with Intent to Incite a Riot or Other Violent Civil Disturbance, and for Other Purposes (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967)

Benjamin Houston, The Nashville Way: Racial Etiquette and the Struggle for Social Justice in a Southern City (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012)

Otto Kerner, et al., Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968)

Malcolm McLaughlin, The Long, Hot Summer of 1967: Urban Rebellion in America (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014)

Gardiner H. Shattuck, Episcopalians and Race: Civil War to Civil Rights (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000)

The liberation school and ensuing controversy were covered in the following editions of The Tennessean, all from 1967: May 21, May 22, June 8, June 18, August 4 through 6, August 9, August 12 through 15, August 17 through 19, August 21 through 24, September 5, September 19, November 8, and November 10

St. Anselm’s Episcopal Church (formerly St. Anselm’s Episcopal Chapel and Student Center) on Meharry Boulevard in North Nashville.

Source: Photograph by Joseph Watson

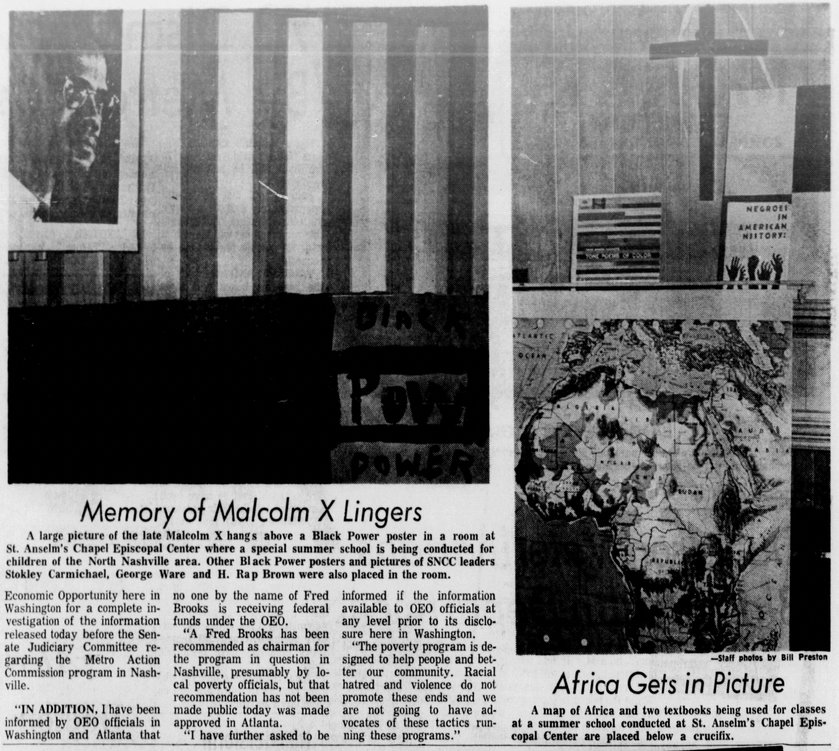

Photographs of St. Anselm’s liberation school, showing, among other things, a portrait of Malcolm X, a map of Africa, and a crucifix.

Source: The Tennessean, August 4, 1967, p. 10

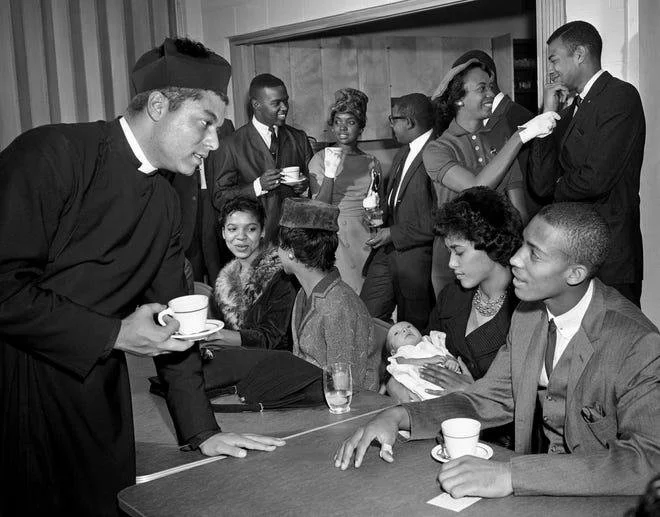

Members of St. Anselm’s Chapel gathering for fellowship after morning worship on October 29, 1961. Rev. James E. P. Woodruff, chaplain of St. Anselm’s, is on the far left.

Source: Photograph by Joe Rudis for The Tennessean, https://www.tennessean.com/picture-gallery/news/local/2021/10/03/nashville-tennessee-middle-tn-october-1961-60-years-ago-photos/5946553001/

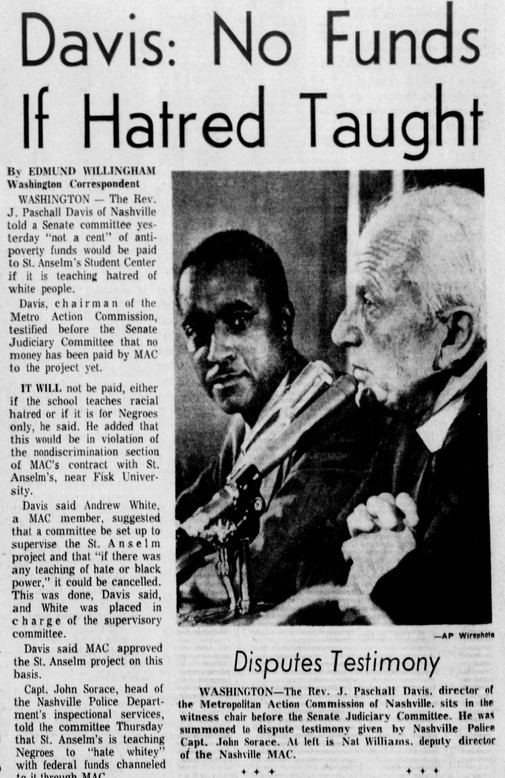

Rev. J. Paschall Davis (right), chairman of the Metropolitan Action Committee, testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee about St. Anselm’s liberation school. On the left is Nat Williams, MAC deputy director.

Source: The Tennessean, August 5, 1967, p. 1