Christ Church’s relationship to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s was, in many ways, the story of a church divided. As the movement unfolded, the vestry repeatedly made clear its support for the racially segregated status quo. Meanwhile, Rev. Raymond T. Ferris, who served as rector from 1954 to 1964, was an outspoken advocate of integration. Several episodes from the early 1950s through the mid-1960s shed light on the conflicted response Christ Church offered to demands for Black equality that remade Nashville, the South, and the nation during these years.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, usually marks the beginning of the modern civil rights movement. In truth, it was more a turning point in an ongoing struggle by African Americans for equal rights since the end of the Civil War. The modern movement began gathering steam in the years after World War II as, among other things, Black servicemembers returned home demanding their full constitutional rights while organizations like the NAACP mounted legal challenges to the Court’s “separate but equal” doctrine, established in its 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision.

In October 1951, as this movement gained momentum, a meeting of Southern Episcopal Church leaders (officially, the Synod of the Fourth Province) urged the University of the South’s School of Theology and other seminaries in the region to admit Black students. Sewanee’s student newspaper reported that the theology faculty generally favored of the recommendation along with a “vast majority” of the student body. The Christ Church vestry disagreed, and within weeks passed a resolution addressed to Rt. Rev. Edmund Dandridge, Bishop of Tennessee and a member of Sewanee’s Board of Trustees, and the University’s executive leadership. It warned “that it would be unwise to allow members of the colored race to attend the University.” The original resolution has been lost, and the summary in the vestry minutes, quoted in full here, provides no context or rationale for this position. When the Board of Trustees met in June 1952, it voted to resist integration at the School of Theology. Eight faculty members, including the dean, and the chaplain resigned in protest of the Board’s decision. The Board reversed course a year later only after fourteen bishops threatened to withdraw their seminarians if the School were not integrated.

Beginning in the mid-1950s, efforts to desegregate schools, eating establishments, and other sites in Nashville were met with sometimes fierce white resistance. Though the integration of Nashville’s public schools proceeded with less violence and vitriol than elsewhere in the South, Black Nashvillians and their allies still encountered crowds of red-faced whites outside formerly all-white schools as well as sporadic acts of terror, like the bombings of Hattie Cotton Elementary School in September 1957 and the Jewish Community Center in March 1958. More organized segregationist efforts, like the Tennessee Federation of Constitutional Government (TFGC)—a local variant of the more widespread White Citizen’s Councils—eschewed street violence in favor of lobbying and propaganda and thus attracted more educated and affluent whites, including at least one Christ Church member. W. Dudley Gale, a prominent local businessman, served frequently on the vestry between 1934 and 1958, including several times as senior warden. He was also founding treasurer of the TFGC. In that role, he wrote fundraising letters characterizing the Brown decision as a “communist plan of forced Federal control” that would inevitably lead to the government forcing “your daughter (or son) [to] marry a negro*.”

If Christ Church’s civil-rights era lay leadership was proving itself to be staunchly segregationist, Raymond T. Ferris, who served as rector from February 1954 until June 1964, provides a marked contrast. Arriving in Nashville just a few months before the Brown decision, Ferris quickly became involved in Nashville’s burgeoning civil rights movement. He joined the Nashville Community Relations Conference (NCRC), which spearheaded efforts to desegregate the city’s public schools in the late 1950s and coordinated the lunch counter sit-ins in early 1960. From the pulpit, Rev. Ferris spoke of racial integration as a moral imperative and, in his role as president of the Nashville Association of Churches, co-authored an August 1957 open letter urging other religious leaders to do the same. The following year, Ferris was asked to join the Fisk University Board of Trustees—one of the most prestigious HBCUs in the nation. To further illustrate Ferris’s commitment to civil rights, two episodes from his rectorship are worthy of additional exploration.

In April 1957, Ferris co-sponsored and spoke at the Conference on Christian Faith and Human Relations at Vanderbilt Divinity School. The event addressed “the practical problems of integration from a Christian viewpoint” and drew 300 church leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr., from multiple denominations across the South. At the conclusion of the conference, Ferris hosted a smaller gathering of Episcopal clergy and laypeople at Christ Church to consider the same issues as they related more specifically to the denomination. The meeting was not widely advertised, and the resulting report not widely circulated, to allow those present to discuss potentially contentious questions “in an atmosphere of frankness and utter honesty.”

While the group addressed a range of topics, from the status of existing efforts toward integration to the preference among some Black churches “to work separately,” the perceived distance between clergy and congregation on the question of integration was a persistent theme. As the report of the meeting summarized, “In general the lay attitude on integration lags far behind that of the clergy and closing this gap is one of the main problems.”

That gap became all too apparent when Ferris hosted an NCRC-sponsored event, “Nashville 1960: Its Problems and Possibilities,” at Christ Church on March 30th and 31st, 1960. The gatherings brought together Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish leaders to discuss solutions to racial and religious prejudice. On both nights the church was packed with people of different races, religions, genders, and political views. The large crowds were likely due to the ongoing sit-ins downtown that electrified the city that winter and spring. Beginning on February 13th, groups of young Black men and women, mostly students, began occupying seats at the city’s all-white lunch counters as part of a coordinated, nonviolent campaign to end racial segregation. Some protests, like those at the Greyhound and Trailways bus stations, occurred just a block or two from Christ Church.

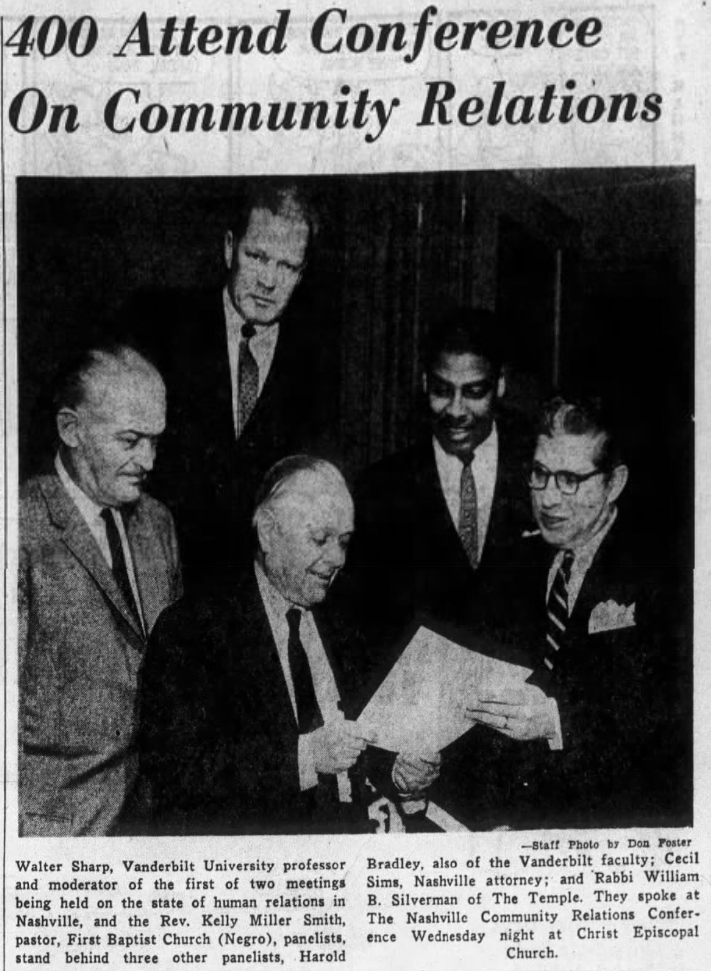

On the first night of “Nashville 1960,” Rabbi William B. Silverman, of The Temple, spoke of anti-Semitism as a “disease” akin to anti-Black racism. Attorney Cecil Sims warned that different races could not be “forced into harmony” and that the sit-ins were an impediment to what should be more gradual change. Rev. Kelly Miller Smith, of First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill, explained the Christ-centered ethos of the sit-ins and addressed the successes and frustrations of the city’s work toward equality, or, as he put it, “the glory and the shame of Nashville.”

The second evening began with a recap of the previous night’s discussion, after which the 400-plus attendees broke into smaller discussion groups throughout the church to consider ways of improving race relations in the city. After more than an hour of discussion, they returned to the nave to deliver recommendations that included gathering better data on public opinions regarding racial segregation, letter-writing campaigns, greater direction and visibility from religious leaders, and more opportunities for interracial and interreligious dialogue.

After months of resistance, most downtown lunch counters quietly integrated in May 1960. The one holdout acquiesced a month later after continued protests. To be sure, the achievement belongs to the young Black men and women who risked arrest and bodily harm in the pursuit of racial parity. The effects of a months-long boycott of downtown businesses by Black Nashvillians and the bombing of city council member and Holy Trinity vestryman Z. Alexander Looby’s house on April 19, 1960, which sparked massive protests, also helped turn the tide in favor of integration. But at least one downtown merchant credited the meetings at Christ Church as helping shift perspectives among white businessmen: “It does make you feel good to know there are at least 500 folks here who are willing to talk about it [race relations] in public.”

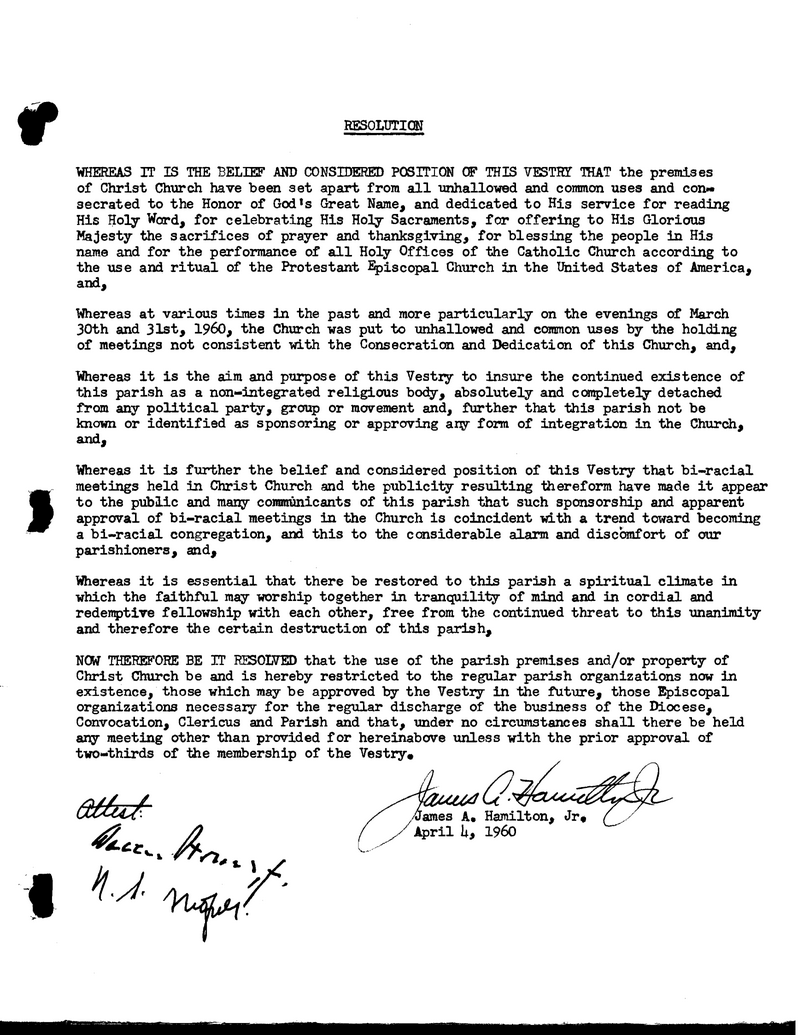

For the Christ Church vestry, the publicity the “Nashville 1960” meetings generated and the small part they might have played in the struggle for equality did not bring the church glory, to borrow Rev. Smith’s words, but shame. At a meeting on April 11, 1960, the vestry considered a resolution denouncing the “unhallowed and common uses” to which the church had been put by hosting the meetings. (It is worth noting that the senior warden had approved Ferris’s use of the church for the meetings. Plus, Christ Church vestry member Alfred D. Sharp’s brother, Walter M. Sharp, was the moderator.) Worried that this could be interpreted as “a trend toward becoming a bi-racial congregation,” the draft resolution proposed to prohibit the use of the church by any outside group except as approved by two-thirds of the vestry. These restrictions were necessary “to ensure the continued existence of this parish as a non-integrated religious body” that would “not be known or identified as sponsoring or approving any form of integration in the Church.”

In the end the vestry voted to approve a version of the resolution that maintained the intent of the draft—restricting use of the church—but excised the explicitly segregationist language. Even so, the issue remained unsettled. An informal discussion on race relations preceded the next vestry meeting. The details of that discussion were not recorded, but the men were at pains to express “love, charity, and unity with one another and with the Rector.” They quietly rescinded the resolution in July. The reason had less to do with a sudden change of heart concerning one of the most pressing social issues of the day than with the likely realization that, according to the Canons of the Episcopal Church, the rector, not the vestry, has the final say in how church buildings are used.

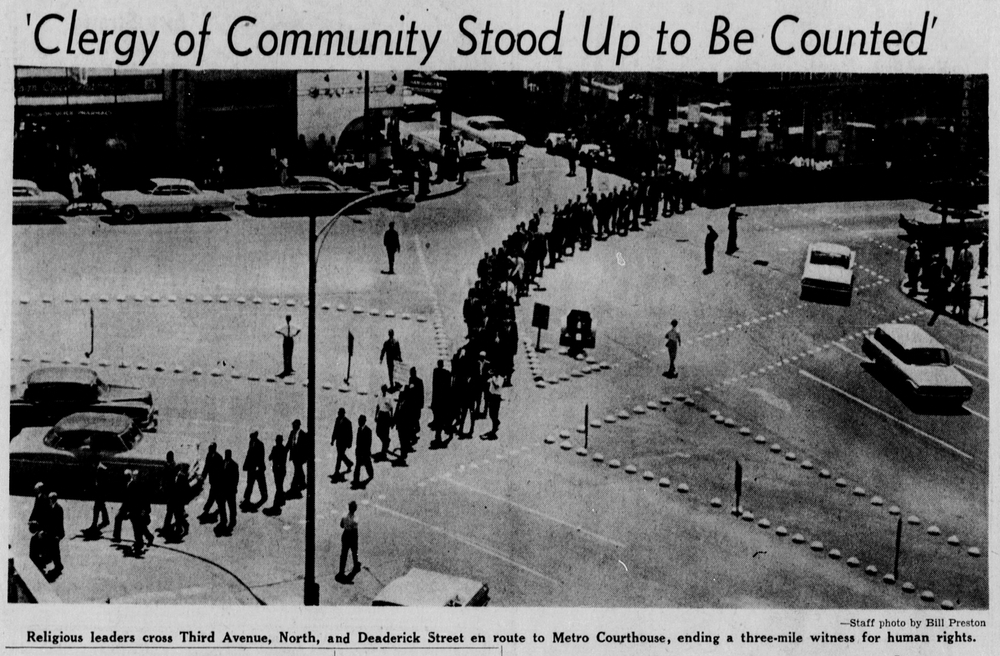

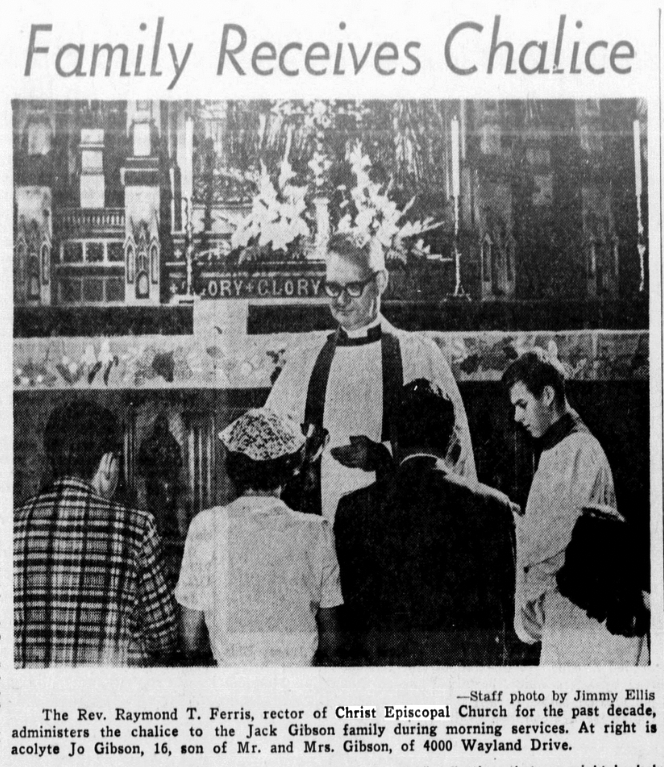

Tensions nonetheless continued to simmer, and Ferris resigned in April 1964. Before departing he participated in a march of 130 religious leaders through downtown as part of renewed demonstrations to continue integrating sites across the city. He also preached a final sermon on Sunday, June 7th, 1964, that channeled the spirit of the civil rights movement. Insisting that God works both within and beyond the Church, Ferris encouraged congregants to “watch where He may be working in current events, and identify with His work wherever you see it.” On the need for ongoing commitment to the struggle for social justice, he insisted, “The kingdom of God is not all here yet. It’s ever dawning; it’s never high noon for the kingdom.”

*There were debates in the early 20th century about whether to capitalize the word Negro, which was a commonly used ethnic descriptor and not a term of disparagement. In his 1899 book The Philadelphia Negro, the sociologist and civil-rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois insisted on capitalizing the term, “because I believe eight million Americans are entitled to a capital letter.” Unsurprisingly, Gale did not to capitalize it.

Note: An earlier version of this article described the draft resolution presented to the Christ Church vestry in April 1960 as though it had been passed.

Sources and Further Reading

The Minutes of the Vestry Meetings, 1960, Christ Church Cathedral Archive, Nashville, Tennessee

The Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation at the University of the South, https://new.sewanee.edu/roberson-project/

David L. Chappell, A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004)

Jimmie Lewis Franklin, “Civil Rights Movement,” Tennessee Encyclopedia (2017), https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/civil-rights-movement/

Benjamin Houston, The Nashville Way: Racial Etiquette and the Struggle for Social Justice in a Southern City (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012)

Gardiner H. Shattuck, Episcopalians and Race: Civil War to Civil Rights (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000)

Jeffrey A. Turner, Sitting In and Speaking Out: Student Movements in the American South, 1960–1970 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010)

Linda T. Wynn, “The Dawning of a New Day: The Nashville Sit-Ins, February 13–May 10, 1960,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 50 (1991): 42–5

Speakers at the first night of the “Nashville 1960” meetings held at Christ Church on March 30th, 1960, from left to right: Harold Bradley, Walter Sharp (standing), Cecil Sims, Rev. Kelly Miller Smith, and Rabbi William B. Silverman.

Source: Nashville Banner, March 31st, 1960, p. 12.

The text of a draft resolution considered by the Christ Church vestry in April 1960 signed by vestry members James A. Hamilton, Jr., Walter Stokes, and N. S. Shofner. The text approved by the vestry did not include the middle four paragraphs but achieved the same ends.

Source: Minutes of the Vestry Meeting of April 11, 1960, p. 71, Christ Church Cathedral Archive, Nashville, Tennessee.

130 religious leaders from across Nashville marching through downtown in support of racial justice on May 5, 1964.

Source: Nashville Tennessean, May 6, 1964, p. 1.

Rev. Raymond T. Ferris delivers communion to Christ Church parishioners during his final service as rector on Sunday, June 7th, 1964.

Source: Nashville Tennessean, June 8, 1964, p. 6.