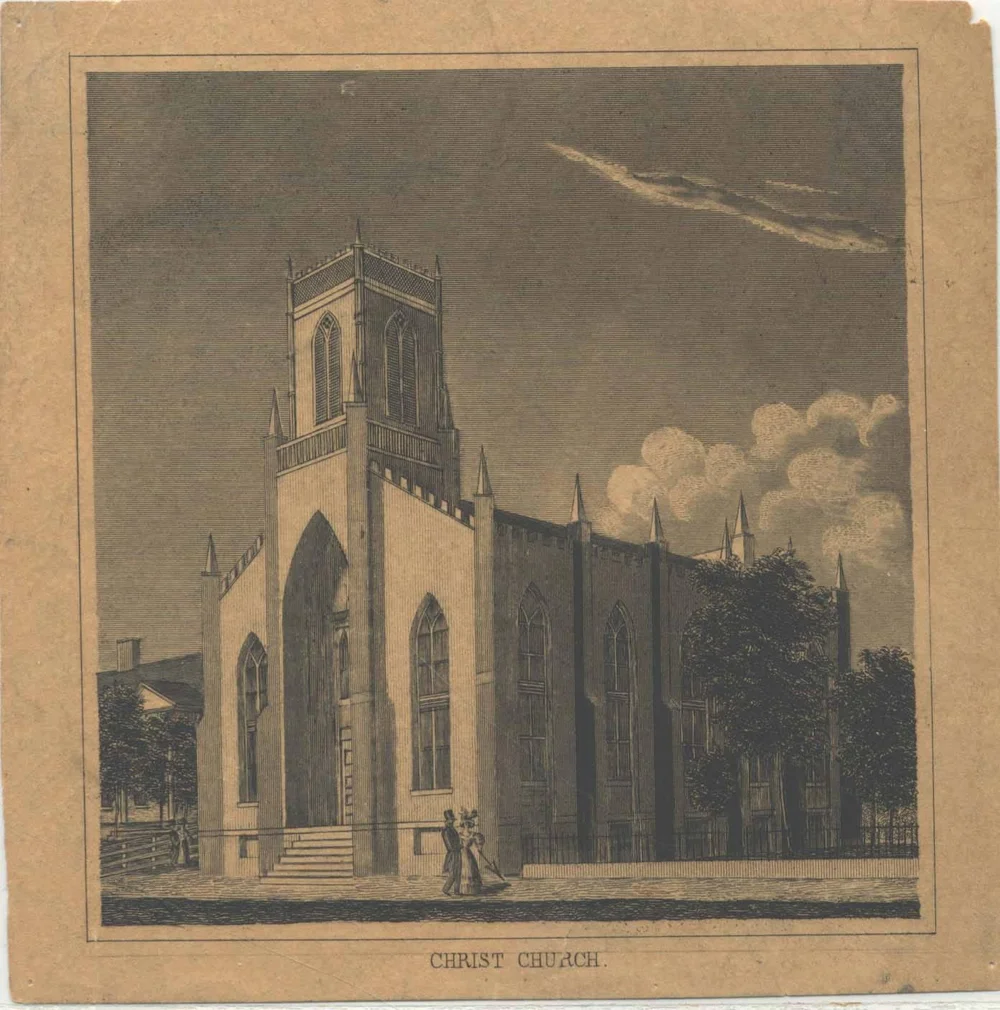

Compared with the current Christ Church sanctuary, dating from the 1890s, the parish’s original home was a modest affair. Built in 1830 at the northwest corner of Spring and High Streets (now Church Street and 6th Avenue), its nave was 55 feet long and 45 feet wide. For comparison, the present church, including the chancel and transepts, is double that size, about 108 feet long and 90 feet wide. The walls were plastered and punctuated by windows filled with red and ochre-stained glass that created a dimly lit interior. In the Church’s official 1929 history, one longtime parishioner recalled windows filled with “browns and yellows.” It was also fairly austere. What little decoration it contained was mostly dark-stained woodwork concentrated in the pulpit, communion rail, altar and reredos, and gallery balustrades. Some of this is visible in the only surviving photograph of the old church’s interior (see below), which shows the altar decorated for Christmas. In a lengthy description of the recently completed building, the National Banner and Nashville Whig described its simplicity and elegance as “a tout ensemble, at once highly beautiful and yet sufficiently chaste and neat.”

The main level of the nave was subdivided into 66 box pews, or seating enclosed by wooden partitions and accessed by a door from one of the aisles. Galleries overhung the space on 3 sides, with an organ and choir loft above the entry at the rear and 12 pews along either side of the nave. This kind of interior arrangement, coupled with a simple stone or brick exterior and a tower marking the main entry, was typical of this era of church building. Similar compositions can be found in churches still standing across the South, although most—like St. Paul’s, Franklin, TN (1831–34); St. James, Wilmington, NC (1837–40); Calvary, Memphis, TN (1843–44); Christ Church, Macon, GA (1851)—have been substantially altered. These drew on older precedents, such as Christ Church, Boston (1723; now commonly known as Old North Church), and Christ Church, Philadelphia (1727–44), that had themselves been modeled on 17th and 18th century parish churches in and around London. Since the only interior image of Nashville’s old Christ Church depicts just the chancel, the photograph of Boston’s Old North Church below gives some sense of the overall scale and composition of the Nashville church, despite the greater illumination of the interior and the neoclassical (rather than Gothic) detailing.

This well-established architectural template also helped reinforce existing social hierarchies, whether Britain’s landed gentry or, in this case, the antebellum South’s caste system. Each of the nave’s box pews was rented by an individual or family. The pews closest to the pulpit and altar fetched the highest prices and conveyed the highest status. Until the 20th century, in the absence of regular offertory collections, pew rents were a primary means of fundraising for churches. Augmented by an annual tax levied by the vestry as well as ad hoc fundraisers, pew rents covered everything from debt payments and the rector’s salary to repairs, operating costs, and other routine expenses.

At the inaugural auction of pews in 1831, the prominent attorney, Christ Church vestry member, and slaveowner Francis B. Fogg paid the highest price—$182.00, or more than $6,300 in 2023 dollars. This, plus the annual tax, bought Fogg and his family exclusive access to the pew for a period of seven years. The cheapest pew rented for $60 (just over $2,000 today), or more than twice the monthly income of most skilled laborers. (The auction rules stipulated that no pew be rented for less than $50.) Less desirable seats in the back and corners of the nave and in the galleries were free, but only pew owners were given a vote in parish meetings. According to another reminiscence in the 1929 history of the church, “places were reserved for the negroes*” in one gallery with “a committee appointed to keep order there.” These seating arrangements ensured the space of the church would mirror the rigid social, economic, and racial hierarchies of the world outside its doors.

This even extended to how worshipers entered the space. They could do so in one of two ways. The main entrance to the church was set eight stone steps up from Spring (now Church) Street through two doors recessed within a grand portal—twelve feet wide, the top of its pointed arch nearly the height of the nave within—at the center of the principal façade. Between these doors and the nave proper was a vestibule spanning the width of the church. This space contained side entrances at street level and corner stairs that provided direct access to the galleries “without interfering with the main entrance,” as the National Banner and Nashville Whig pointedly observed. This ensured that wealthy white parishioners did not have to cross paths with Black (and poor white) worshipers as they passed through the main entry on the way to their rented pews.

The beauty and simplicity of the original Christ Church’s Gothic interior was a testament to its architect’s aesthetic sensibilities, its builders’ skill, and its founders’ sincere faith. The divisions of the interior, which determined where someone could sit and how they might get there, also made the space into a microcosm of the South’s plantation economy.

*There were debates in the early 20th century about whether to capitalize the word Negro, which was a commonly used ethnic descriptor and not a term of disparagement. In his 1899 book The Philadelphia Negro, the sociologist and civil-rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois insisted on capitalizing the term, “because I believe eight million Americans are entitled to a capital letter.” The authors and editors of Christ Church’s 1929 history elected not to capitalize it.

Sources and Further Reading

“Episcopal Church,” National Banner and Nashville Whig, July 4, 1831

Fletch Coke, “Christ Church, Episcopal, Nashville,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 38, no. 2 (Summer 1979): 141–157

James Patrick, Architecture in Tennessee, 1768–1897 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1981)

“Pew Rents,” in An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church, ed. Don S. Armentrout and Robert Boak Slocum (New York: Church Publishing Incorporated, 2000), https://www.episcopalchurch.org/glossary/pew-rents/

Louis P. Nelson, The Beauty of Holiness: Anglicanism and Architecture in Colonial South Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009)

Anne Rankin, ed., Christ Church, Nashville, 1829–1929 (Nashville: Marshall & Bruce, 1929)

Dell Upton, Holy Things and Profane: Anglican Churches in Virginia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997)

The chancel of the old Christ Church decorated for Christmas, showing some of the woodwork around the altar and chancel rail.

Source: Anne Rankin, ed., Christ Church, Nashville, 1829–1929 (Nashville: Marshall & Bruce, 1929), facing p. 124

Christ Church (more commonly known as Old North Church), Boston, built in 1723 and photographed around the turn of the 20th century, is similar in composition to Nashville’s old Christ Church, with its box pews and galleries, despite its neoclassical detailing.

Source: “Boston, Christ Church, (Old North Church), Interior,” photograph by Halliday Historic Photograph Co., ca. 1890–1910, Boston Pictorial Archive, Boston Public Library, Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/3j335t70f

An engraving of the old Christ Church. One of the side entrances leading directly to the galleries is visible around the corner from the main entry just to the right of the two very well-dressed pedestrians.

Source: “Christ Church Episcopal Engraving,” Library Photograph Collection, Drawer 16, Folder 23, ID# 3063, Tennessee State Library and Archives