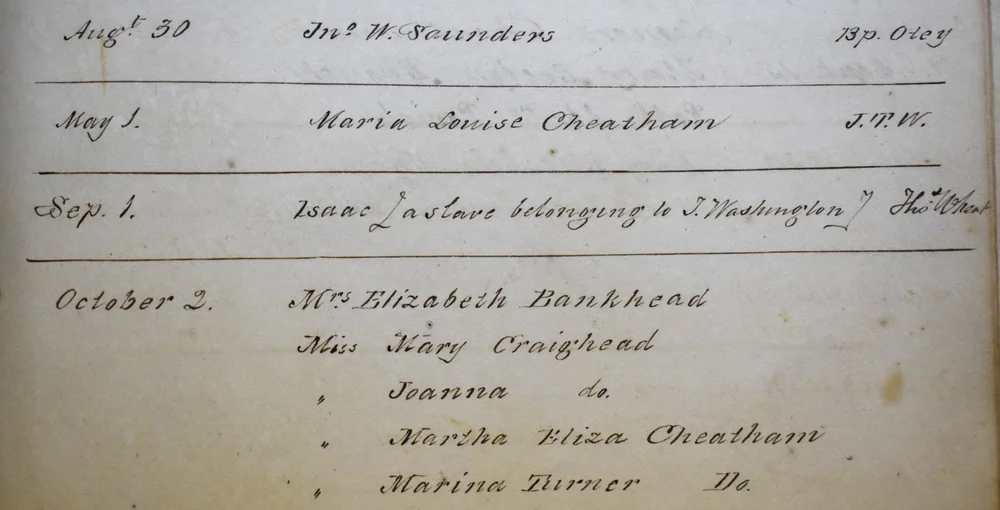

Isaac, namesake of the Isaac Project, was an enslaved Black man who lived in Nashville in the first half of the nineteenth century. In recent years he has become known to Christ Church parishioners as the first and only person described as a “slave” in parish records to have received the sacrament of baptism. The notation in the parish baptism register dated September 1, 1842, describes him as “Isaac (a slave belonging to T. Washington).” His baptism into the body of Christ – even as he remained a slave to another member of Christ’s church – symbolizes the fraught, contradictory, and complex relationship between slaves and masters in antebellum Nashville, and between whites and Blacks more generally in the context of the Christ Church and larger Episcopal and Christian communities. In a real sense, the Isaac Project’s quest to understand Christ Church’s relationship with race begins with Isaac. Discovering Isaac’s story has not been easy, given the relative scarcity of surviving historical documents about individual enslaved persons in the antebellum South. Nevertheless, we have learned a number of basic facts about him, which we have tried to place into context in this report.

Isaac was born into slavery, probably between 1804 and 1807. We are not sure exactly where he was born, who his parents were, and who was his first enslaver. By the late 1820s, Isaac was owned by Dr. James Roane, a prominent Nashville physician and son of Archibald Roane, who had been the second Governor of Tennessee in 1801-1803 and after whom Roane County, Tennessee, was named. Isaac is described in documents from the years 1828-1833 as a slave of Dr. Roane, including documents that show Isaac was a carpenter by trade.

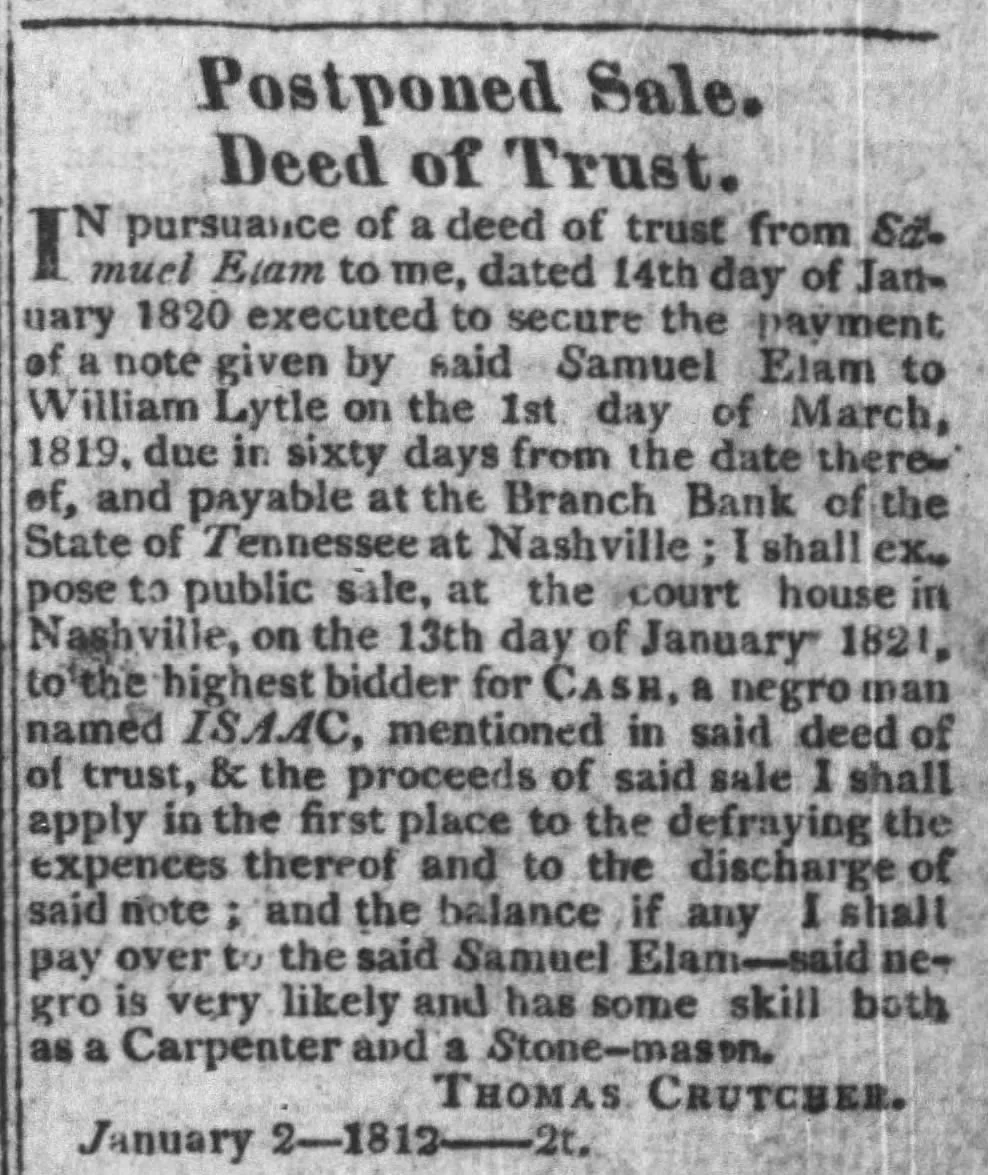

Isaac’s biography before this point is largely unknown. It is possible that Isaac is the person mentioned in an advertisement for an auction in January 1821, when a certain Isaac was put up for sale at the Nashville courthouse to cover a debt owed by a slaveholder named Samuel Elam. The advertisement noted that this Isaac “has some skill both as a Carpenter and a Stone-mason.” If this was the same Isaac later enslaved to Dr. Roane, he would have been about fourteen to seventeen years old. However, a search of Davidson County property records has so far yielded no evidence that Mr. Elam’s Isaac was sold to Roane.

The Roane household in the late 1820s and early 1830s included Dr. James Roane and his wife Anne, two young daughters named Christiana and Laura, and a little boy named Archibald. Also living in the household was Mrs. Ann Campbell Roane, the doctor’s widowed mother and former First Lady of Tennessee, who would pass away in 1831 at the age of seventy-one. According to the U.S. Census of 1830 and Davidson County property records, the six white members of the Roane family were outnumbered by their enslaved servants. The number of slaves varied as some died and others were born, but generally totaled eight to twelve people. These included Isaac, then in his mid-20s, and another adult male slave who was at least a decade older. Of the adult women slaves, Hannah seems to have been the oldest, described as “about forty” in a document from 1832 and “about fifty” in 1833. Susan may have been about the same age as Hannah. She was described as “about fifty” in 1833, but she had a daughter Mary who was only eight at the time, so she might have been a little bit younger. Susan also had a young son named Levi. Jinsey (or Ginny in some records) was a woman about Isaac’s age or a little younger. She had four children that we know of: Byron, born about 1824, William (about 1828), Phil (about 1831), and a fourth child born in 1833. The youngest adult female slave was Emily, who at the age of seventeen in 1832 had an infant child.

As is so often the case with enslaved mothers and their children, the official records tell us nothing about the fathers. Slaves would marry one other, of course, but their marriages were not usually recognized or recorded by the local government or white-dominated churches, including Christ Church in Nashville. Legal marriage was one of the many rights denied to enslaved persons in the United States. The lack of legal recognition for slave marriages made it much easier for slaveowners, slave traders, executors of slaveowner estates, and other members of the slaving elite to break up slave families whenever this was convenient or profitable. We must also remember that the rape of female slaves by their white male owners was not uncommon and that a good number of enslaved children were the result of this practice.

We know little of the personal relationship between James Roane and Isaac, but it is clear from surviving documents that Dr. Roane saw Isaac, already developing into an able craftsman and carpenter, as a significant investment and potential source of revenue. Roane is known to have hired Isaac out, at least according to a deed dated March 7, 1829. This was a common arrangement by which some or all of Isaac’s wages would have ended up in Roane’s pocket. James Roane and his family were not members of the new Episcopal church in Nashville, but it is quite possible that Roane hired out Isaac to work on the construction of the first Christ Church building in 1830-31.

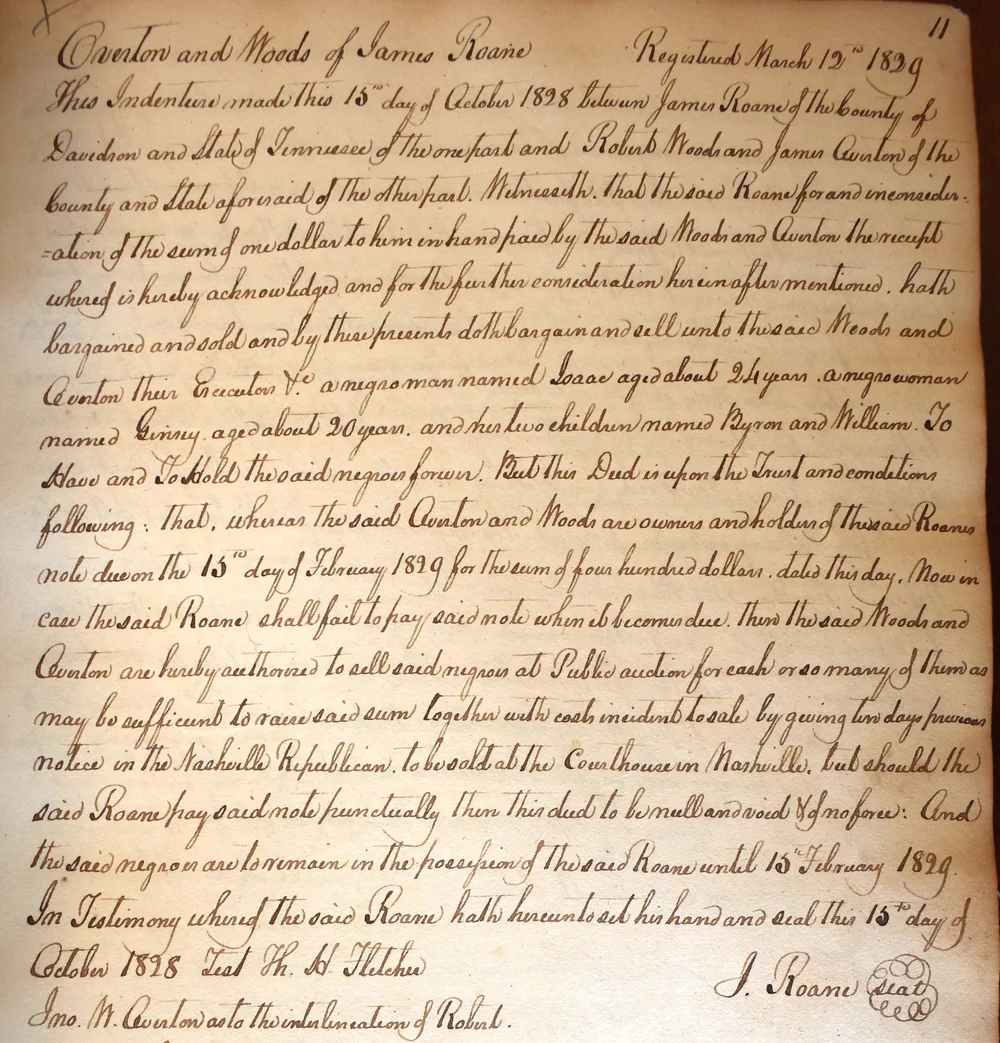

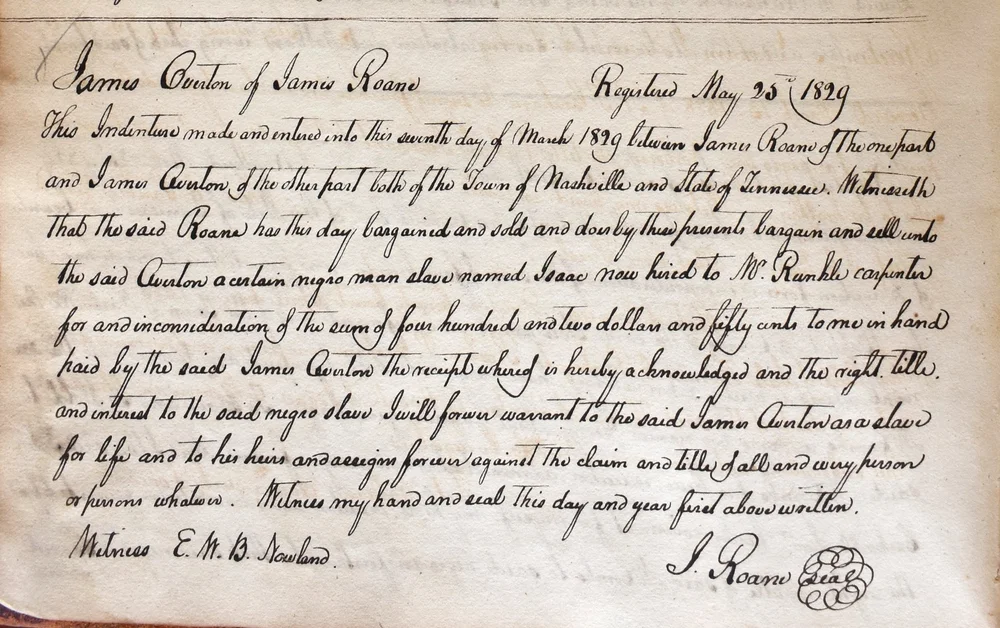

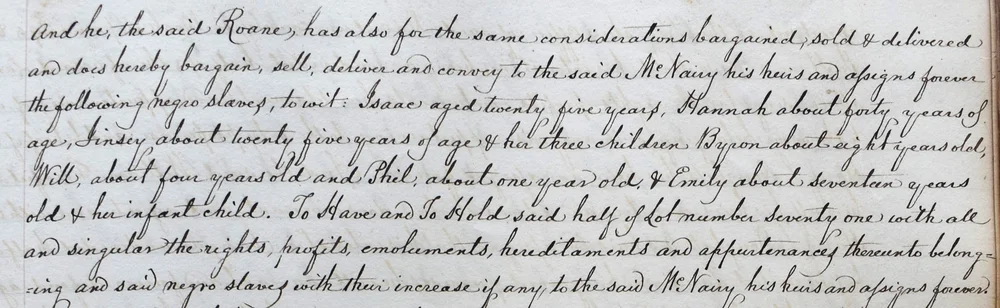

Aside from renting out Isaac and garnering his wages, Roane found other ways to profit from his possession of slaves. On at least two occasions, Roane used Isaac and his other slaves as collateral for a loan. Sometime in the fall of 1828, for instance, James Roane borrowed $400 from Robert Woods and James Overton of Nashville. On October 15, 1828, in order to settle this debt, Dr. Roane gave Woods and Overton a note for $400 that would come due on February 15, 1829. On the same day, he also deeded to them, for the sum of one dollar, “a negro man named Isaac aged about 24 years, a negro woman named Ginny aged about 20 years, and her two children named Byron and William.” These slaves were to remain in Roane’s possession, but if he failed to pay the $400 when it came due the coming February, Woods, and Overton would be entitled to sell the slaves at auction at the Nashville courthouse in order to cover the $400 note. It appears that Roane was unable to pay the $400, although there was no public sale. Instead, we find in the archives a deed dated March 7, 1829, according to which James Roane agreed to sell to James Overton “a certain negro man slave named Isaac now hired to Mr. Runkle carpenter” for the price of $402.50. Even though this deed was recorded at the Davidson County courthouse, it seems that the sale was never completed. Just three years later, in August 1832, we find Isaac still in Roane’s possession, when the doctor again mortgaged Isaac, along with a parcel of land and seven other slaves (Hannah, Jinsey, Jinsey’s children Byron, Will, and Phil, and Emily with her infant child), for the sum of $2250. In this case, Roane must have paid back the loan, since all these slaves remained in his possession.

**********

Dr. Roane died on February 27, 1833, from cholera which he contracted while treating patients during an epidemic of the disease. Obituaries in Nashville papers praised his self-sacrifice, medical skill, gallantry, and erudition (his estate included a library of over five hundred books). But Roane also left significant debts, which his wife and young children, or rather the executor of his estate Samuel Watson, were unable to cover. Virtually all of Dr. Roane’s personal property was auctioned off – his furniture, his books, and his slaves. The date of the public auction of the slaves was set for Saturday, October 12, 1833, between nine and ten in the morning, to take place on the public square of Nashville. An advertisement that ran in Nashville papers for several weeks in advance of the sale noted that one of the slaves was a “valuable Carpenter.” Isaac was thus the main attraction for this particular auction. The auctioneer was named John Estill and he earned a commission of $50 for his services.

The auction followed the common custom of selling individual adults separately, while small children were kept with their mothers. Roane’s twelve slaves, who had lived together under one roof, were distributed to six different owners. Any marriages that might have existed among them, for instance between Isaac and one of the women, were disrupted. The prices paid at slave auctions give us insight into the minds of Nashville’s slave owners as they evaluated the enslaved persons before them, ranking them according to their perceived benefit and usefulness as shown by such features as age, health, gender, skills, docility, and expected longevity. Young women were also evaluated for childbearing potential and attractiveness, particularly when buyers were interested in having them as sexual partners. In this particular auction, most of the purchasers had connections to Christ Church, a sign of the extensive interpenetration of the new Episcopal parish with Nashville’s slaveholding elite. By the way, the executor of Roane’s estate, Samuel Watson, also had Christ Church connections: his brother Matthew Watson was a founding member and vestryman for most of the period from 1830 to 1865, while Samuel himself would have two children baptized at the church some years later in 1849.

The auction in October 1833 scattered the small community of James Roane’s slaves to the four winds. Hannah was purchased for $300 by Henry Adolphus Rutledge, a founding member of the Christ Church parish in the 1820s and a payer of pew rent in 1831. His father was Henry Middleton Rutledge, at that time a vestryman at Christ Church, while his grandfather, Edward Rutledge, had been a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Henry Jr.’s sister Mary was married to longtime Christ Church vestryman Francis B. Fogg. The enslaved woman Hannah had little time to settle into life in a Christ Church household, however, since Henry Jr. soon moved his family to a plantation in Talladega County, Alabama, where he is recorded as owning 31 slaves in 1840 and 62 in 1850. It is unclear whether Hannah remained a house slave or was sent to work in the fields at the plantation.

Emily and her infant child, then aged about eighteen months, were sold for $450 to Ephraim P. Shall, son of George Shall who had paid pew rent at Christ Church in 1831. Like Hannah, Emily spent little time associated with the Episcopal parish in Nashville. Within a few years, the entire Shall family moved to New Orleans, where George Shall was proprietor of the City Hotel and owner of 43 slaves, according to the 1840 census. Emily may have remained Ephraim’s household servant or may have been put to work at the family’s hotel.

Susan’s son Levi was apparently old enough not to be considered dependent on his mother for survival, so he was sold separately. His purchase price is listed in county documents as $545, but since the bill of sale has not been located in the Davidson County archives, we do not know who bought him. His mother Susan and sister Mary, meanwhile, found themselves in the hands of Robert Coleman Foster, who had paid $600 for the pair. This Foster was the father of Christ Church parishioner Ephraim H. Foster, who paid pew rent in 1831 and had seven of his own children baptized at the church during the 1830s. The elder Foster passed away in 1844 and his last will and testament did not name any of his slaves, so we lose track of Susan and Mary at this point.

At the time of the auction, Jinsey was in her mid-twenties and had four young children: Byron (about 9), William (about 5), Phil (about 2), plus a newborn. All five were purchased together for $585 dollars by Edward Hall, the only purchaser who did not have a close Christ Church connection. We do know that he was involved in the grain trade in Nashville and is listed as owning four slaves in 1830, nine in 1840, and three in 1850.

*********

Isaac’s new owner was Thomas Washington (1788-1863), a local lawyer, landowner, and communicant at Christ Church. Washington and his wife Mary had been among the earliest members of the nascent Episcopal community in the mid-1820s and would remain faithful members until the end of their lives. Mary Washington (1803-1867) held the important position of treasurer of the Parish Aid and Sewing Society, which held many successful fundraisers for the church. She and her three daughters were active parishioners at Christ Church down to the end of the nineteenth century and beyond. All three of the daughters are memorialized in the Nave of Christ Church: Sarah Allibone Osborne Washington Nichol (1824-1894, the lectern), Jeannette Love Washington Woods (1835-1918, a window in the baptistry), and Maria Adelaide Washington Kirkman (1832-1892, two lancet windows formerly under the great wheel or rose window, but in storage since the installation of the organ in the balcony in 2003).

After the previous five years of James Roane’s ownership, with repeated mortgaging and the constant threat of sale, life in the Washington household brought relative stability, at least from a legal standpoint. Thomas Washington was involved in multiple land transactions and slave purchases in the 1830s and 1840s – both as an individual and as a partner in the law office of Washington & Hays – but he rarely put up his own slaves as collateral. This means that the names of Thomas Washington’s slaves show up less frequently in official government records. To the best of our knowledge, Isaac’s name ceases to appear in Davidson County legal documents after his purchase by Thomas Washington in 1833. Indeed, the only written information we have about Isaac in this later period is the church record of his baptism in 1842.

What can we say about Isaac’s life in the Washington household? At the time of his purchase, Isaac was roughly twenty-six to twenty-nine years old. Thomas Washington had bought him for the princely sum of $1,052, no doubt in recognition of Isaac’s carpentry skills, so it is quite likely that Isaac was kept busy working his craft for the benefit of the Washington family. He was likely hired out from time to time, just as he had been with James Roane. Washington had recently gotten married, in 1831, to the young widow Mary Allibone Osborne, who brought her six-year-old daughter Sarah into the family. Thomas and Mary had three children of their own, two of them while Isaac was part of the household: Maria Adelaide (1832), Jeannette Love (1835), and Thomas Lawrence (1840). This growing family required – from an elite slaveholder perspective, of course – the acquisition of an enslaved household staff. Mr. Washington had owned just one slave as a bachelor in 1820, but this number grew to nine by 1840. This staff was scaled back to five in 1850 and six in 1860 (we can’t yet find Washington’s record in the 1830 census).

We know the names of a few of these slaves. One was Lavinia, commonly called Viney, whom Washington purchased in 1835 when she was in her mid-to late twenties, apparently as nursemaid and nanny to the young children. She would continue to live with the Washingtons and then their adult daughters until her death in 1899. A document from 1843 indicates that besides Viney the household slaves included a man named Alfred, a woman Marinda with her sons Peter and Henry, a girl named Rosetta, and perhaps others. In addition, Thomas Washington owned a farm outside Memphis in Shelby County, Tennessee, where he owned at least twenty-two slaves in 1843. It is possible that Isaac spent part of his time at the Washington farm in western Tennessee.

Aside from this general context, we know little about Isaac’s life as a slave to Thomas and Mary Washington during the decade between his purchase and his baptism at Christ Church. We do not know what sort of owners the Washingtons were, whether they were lenient, or cruel, or indifferent. We know nothing about his day-to-day activities or his relationships with the other enslaved people in the household and with the Washington children. We do not know whether Isaac married or fathered any children himself.

The only thing we know for certain is that on September 1, 1842, “Isaac (a slave belonging to T. Washington)” was baptized by the Rev. J. Thomas Wheat, rector of Christ Church and that this fact was noted in the official parish register. This record tells us much and little at the same time. With his baptism, Isaac became the second of just fourteen slaves who would receive a Christ Church baptism over all the years of Southern slavery, a period when parishioners of the church-owned many hundreds of slaves. Isaac’s baptism is also the only case in the history of the parish where the record describes the baptized person as a “slave” rather than using the common euphemism of “colored servant.” Thomas Washington, for his part, entered the ranks of just eight slaveowners at Christ Church who brought a slave forward for baptism. By way of comparison, the rector and eleven vestrymen who served in 1840 owned between them exactly 100 slaves, yet none of them had any of their slaves baptized at Christ Church. The slaveowners who ran Christ Church included Rev. J. Thomas Wheat himself, the man who performed two baptisms of slaves during his time as rector of Christ Church (1837 to 1848): Mary Jane in 1841 and Isaac in 1842. Rev. Wheat is known to have owned at least four slaves during his time as rector, three who were recorded in the 1840 census and a fourth named Daniel, a short-sighted boy of sixteen, whom Wheat purchased in 1845 for $50. Whatever kindness the rector may have believed he showed to his slaves, this did not extend to their complete membership in the church community of which he was a part. Powerful forces of exclusion and separation were clearly at work.

We know little about what brought Isaac to the moment of baptism. Isaac would have been in his mid- to late thirties at this point. Adult baptisms were not uncommon among white parishioners, though infant and child baptisms were the norm. Among those slaves who were baptized, nearly all experienced the sacrament as adults. Theological inquiry and genuine religious conversion may have played a role here. This was no “forced conversion,” but something that the slaves themselves may have requested and even – within the constraints forced upon them by their legal status – insisted upon.

It is also possible that Isaac was deathly ill at the time and that this might have prompted the baptism. Deathbed baptisms show up in Christ Church records with depressing frequency. Yet we have no death record to pair with Isaac’s baptism, so we remain uncertain. Indeed, at this point in our research, we have found no records at all mentioning Isaac in the years after his baptism in 1842. Could Isaac have escaped and tried to reach freedom in the North? A search of Nashville newspapers from 1842 to 1865 has not turned up any “runaway slave” postings where Thomas Washington sought Isaac’s return. Could Isaac have been sold to another owner? A search through the unindexed Davidson County deed records of the years after 1842 has so far turned up no record of Isaac’s sale, though this search is ongoing. Could Isaac have been emancipated? The Metro Davidson County archives seem to have no record of this. Could Isaac have died soon after the baptism? Searching through the Davidson County Cemetery Survey and the records of Mount Olivet, Mt. Ararat, and Nashville City Cemeteries has yielded many records of men named Isaac, but none that seem to be a good match for Isaac the enslaved carpenter.

A suggestive clue is provided by a deed of mortgage dated August 24, 1843. At this time, Thomas Washington put up a large number of his slaves as collateral for a loan of $3500 from John M. Bass and Daniel Graham. The purpose seems to have been to finance a large purchase of land which Washington accomplished in September 1843 together with his law partner Preston Hays. As was the case with the earlier mortgages by James Roane, the deed enumerates the slaves to be mortgaged. These included six household slaves held by Washington at his home in Nashville (Alfred, Viney, Marinda, Peter, Henry, and Rosetta), as well as twenty-two slaves “in the possession of Thomas Moorhead [presumably an overseer] on my Farm in Shelby County in Tennessee.” These farm slaves included six adult males. The significant detail here is that Isaac is not mentioned among either group of slaves. It is possible that Washington declined to mortgage Isaac because of his importance and skills, or because Isaac was someone that Washington could not possibly do without in case of his failure to pay the mortgage. Yet this somehow seems unlikely, given that Washington was willing to risk seven other adult male slaves as well as Viney, the nanny who was taking care of his own children. It seems more likely that Isaac had passed away sometime between his baptism in September 1842 and the date of this deed nearly a year later. This deed is indirect evidence which we hope will be confirmed (or refuted) in the future with more direct information, but this is currently the best evidence we have about what may have happened to Isaac.

Isaac Project researchers still have many unanswered questions about Isaac. But perhaps more important are the questions that his story may inspire among the readers of this report as our parish continues to reflect on how the church and its members have historically benefitted from and been complicit in systems of oppression rooted in anti-Black racism and white supremacy.

Sources and Further Reading:

“Overton and Woods of James Roane, Deed of Trust” (15 October 1828, registered 12 March 1829). Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book T (1829-33), page 11.

“James Overton of James Roane, Bill of Sale” (7 March 1829, registered 25 May 1829). Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book T (1829-33), pages 16-17.

“Boyd McNairy of James Roane, Deed of Trust” (19 August 1832, registered 8 December 1832). Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book V (1832-34), pages 52-53.

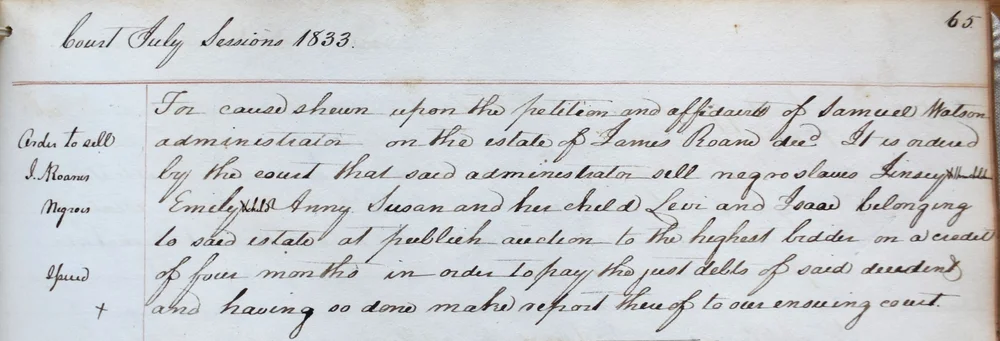

“Order to sell J. Roane’s Negroes” (24 July 1833). Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Circuit Court Minute Book (1833-34), page 65.

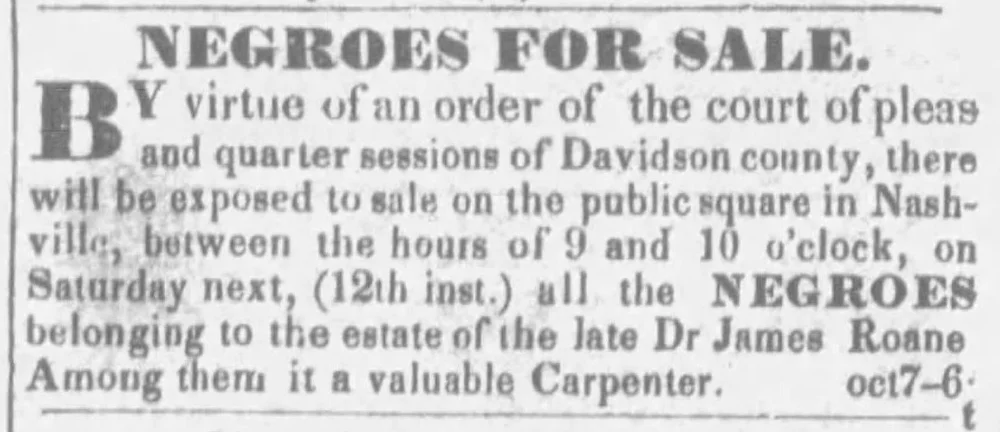

“Negroes for sale.” National Banner and Daily Advertiser (Nashville), October 9, 1833.

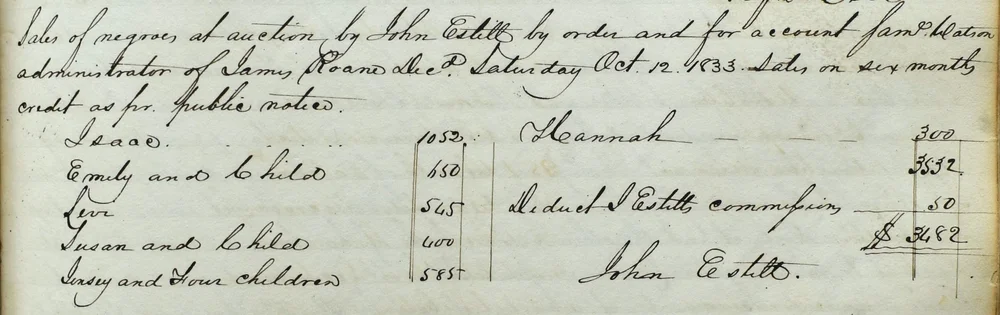

“James Roane Dec’d Sale” (recorded 27 November 1835). Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Wills, Book 10 (1832-36), pages 251-257.

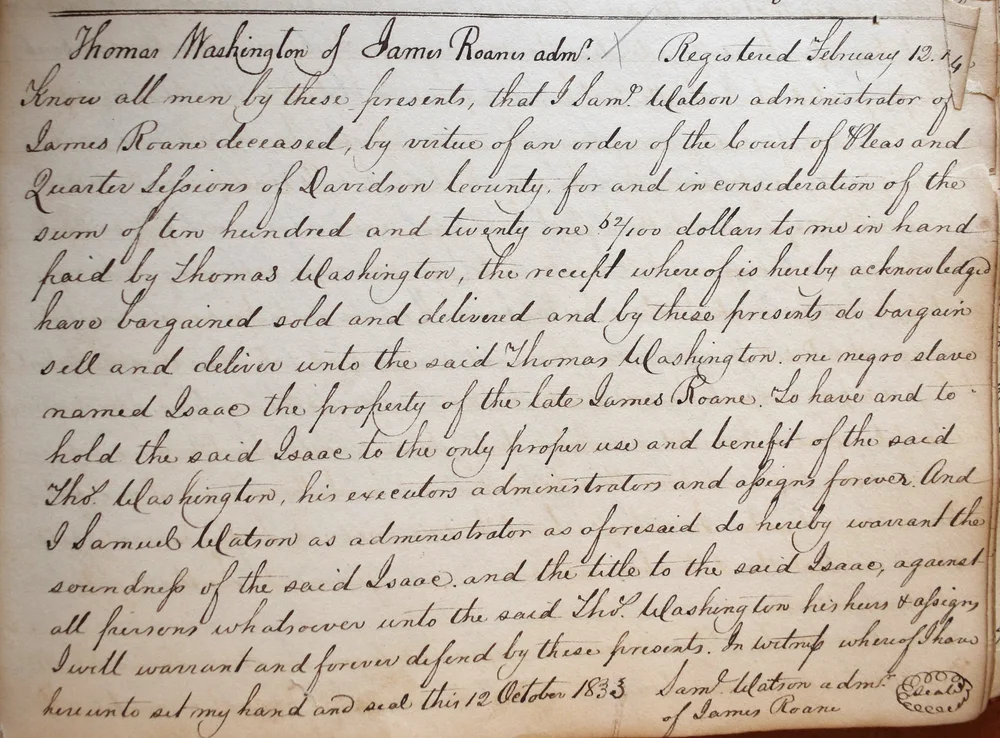

“Thos. Washington of James Roane Adm., Bill of Sale” (12 October 1833, registered 12 February 1834). Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book W (1833-35), pages 187-188.

“Washington & Hays of J. Andrews, Bill of Sale” (7 May 1842, registered 10 May 1842). Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book 5 (1842-43), page 70.

Baptism of Isaac (1 September 1842). Parish Register #1 (1829-1848). Christ Church Cathedral Archive, Nashville, Tennessee.

“J. M. Bass of T. Washington, Deed of Mortgage and Supplement” (24-28 August 1843, registered 29 August 1843). Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book 6 (1843-44), pages 213-214.

“J. T. Wheat of J. Gregory, Bill of Sale” (23 August 1845, registered 19 September 1845). Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book 8 (1844-45), page 176.

Advertisement for the sale in 1821 of a slave named Isaac, “a Carpenter and a Stone-mason.” He may have been the same man as the Isaac later baptized at Christ Church in 1842, but this cannot yet be confirmed. Source: The Clarion and Tennessee State Gazette (Nashville), January 9, 1821, p. 3

Dr. James Roane used Isaac and three other slaves as collateral for a $400 loan. This document, dated 15 October 1828, describes Isaac as “a negro man named Isaac aged about 24 years,” suggesting he was born around 1804. Source: Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book T, p. 11

James Roane agreed to sell Isaac to James Overton for $402.50 in March 1829, but sale seems not to have gone through. Source: Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book T, p. 16

Portion of a deed of trust, dated August 29, 1832, by which James Roane mortgaged to Boyd McNairy and Isham Dyer a portion of land as well as “Isaac aged twenty five years” and seven other slaves. This document asserts that Isaac was born around 1807. Source: Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book V, p. 53.

Portion of a deed of trust, dated August 29, 1832, by which James Roane mortgaged to Boyd McNairy and Isham Dyer a portion of land as well as “Isaac aged twenty five years” and seven other slaves. This document asserts that Isaac was born around 1807. Source: Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book V, p. 53.

Portion of a deed of trust, dated August 29, 1832, by which James Roane mortgaged to Boyd McNairy and Isham Dyer a portion of land as well as “Isaac aged twenty five years” and seven other slaves. This document asserts that Isaac was born around 1807. Source: Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Register of Deeds, Book V, p. 53.

Portion of the Davidson County record of the sale of James Roane’s estate showing the prices paid for his twelve surviving slaves. Source: Metro Davidson County Archive (Nashville, Tennessee), Wills, Book 10, p. 257.

Bill of Sale by which Thomas Washington bought “one negro slave named Isaac the property of the late James Roane” on October 12, 1833.

Christ Church parish register showing the baptism of Isaac on September 1, 1842. His name is listed amidst the records of baptisms of adult white parishioners. Source: Parish Register #1 (1829-1848). Christ Church Cathedral Archive, Nashville, Tennessee.