Most members of the early southern planter class were transplants from England and thus also members of the Anglican Church. Twelve years after the founding of Jamestown in 1607, a ship carrying more than twenty enslaved Africans landed on Virginia’s shores. In 1667, the colonial assembly declared: “[Even if] by the charity and piety of their owners. . . the conferring of baptisme doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedome.” Thus began the counter-intuitive practice of extending spiritual freedom, represented by baptism, while also perpetuating a system of chattel slavery.

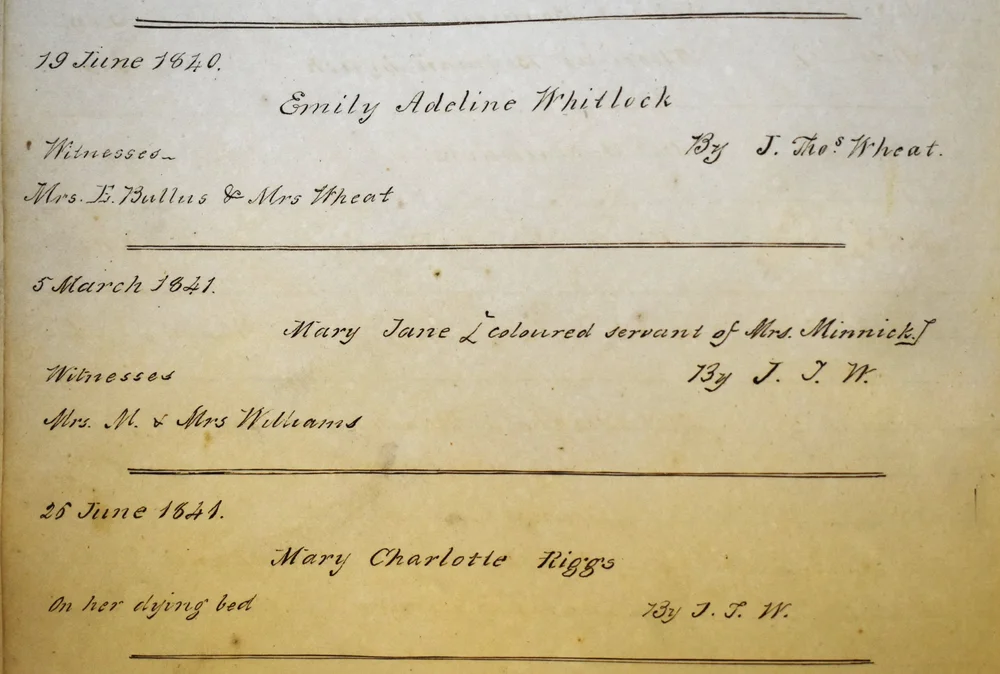

At Christ Church in Nashville, the Reverend J. Thomas Wheat baptized Mary Jane, who was described in the baptismal record as the “coloured servant of Mrs. Minnick,” on March 5, 1841. The sponsors/witnesses at the baptism were listed as “Mrs. M. and Mrs. Williams.” Mary Jane’s baptism is the earliest on record for an enslaved person or person of color at Christ Church.

Mary Jane’s owner – and a witness at the baptism – was Mrs. Ann Green Minnick (c. 1773-1849). Mrs. Minnick was a founding member of the parish in the late 1820s along with her husband Dr. Joseph Planta Minnick (1770-1835). Census documents reveal that the Minnick family owned three slaves in 1820 and seventeen in 1830. By 1841, Mrs. Minnick was widowed and, we believe, living with her daughter Maria Minnick Shelby and her son-in-law, the famous and very wealthy Dr. John Shelby. The “Mrs. Williams” who served as a sponsor at Mary Jane’s baptism is most likely Priscilla Douglass Shelby Williams (c. 1815-1893), daughter of Dr. Shelby and granddaughter of Mrs. Minnick.

We know little else about Mary Jane. Since hers was an “adult baptism,” we can presume that she was at least a teenager in 1841 and probably born no later than 1825 or so. We can infer that she was part of the community of a dozen or more slaves who were part of the Shelby-Minnick household in the early 1840s.

Records of slave baptisms are rare in the parish register, totaling only fourteen persons out of the more than nine hundred Christ Church baptisms performed in the four decades between the church’s founding and the end of slavery in 1865. Over the same period we find only three confirmations of enslaved persons and five slaves described in parish records as “communicants” of the church. This was a period when white parishioners of Christ Church, taken together, owned many hundreds of slaves. Free persons of color were even more poorly represented in parish records in the years before 1865. We know of only two baptisms and one confirmation, all of them on a single day of prison ministry at the Tennessee penitentiary in 1850, when two African Americans were among a dozen inmates baptized by Rev. Charles Tomes and his assistant Joseph H. Ingraham. We also know of two marriages involving “free coloured” persons – one in 1840 and another in 1861.

Among the white members of the early Christ Church community, baptism usually signified a major step in one’s religious development, leading towards confirmation and full membership in the church community. It was a ubiquitous rite of passage, so important that it was routinely administered to those who were mortally ill and seemed likely to die. Among persons of color in the orbit of Christ Church, by contrast, baptism, confirmation, and even Episcopal church membership were not unknown, but neither were they common or widely encouraged by the church as an institution. Enslaved persons and free people of color, for their part, largely sought their spiritual satisfaction elsewhere, outside what they must have seen as the slaveholders’ church. With some occasional and interesting exceptions, this spiritual and religious chasm remained the pattern throughout the four decades that Christ Church was intimately tied up with the slave system, and for many years beyond. Looked at another way, however, the baptism of Mary Jane in 1841, just ten years after the construction of the first Christ Church sanctuary, reminds us that people of color have been part of the Body of Christ and the community of Christ Church since the very earliest days of the parish, however qualified their membership may have been in the eyes of their enslavers.

Sources and further reading

Christ Church Baptisms Complete Spreadsheet. https://sites.google.com/a/www.christcathedral.org/archives/history/church-registers

Parish Register #1 (1827-1848). Christ Church Cathedral Archive, Nashville, Tennessee.

Hannah-Jones, Nikole. “The 1619 Project” The New York Times, posted August 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html.

Schjonberg, Mary Frances. “Baptizing child of early enslaved Africans helped tie Episcopal Church to slavery’s legacy.” Episcopal News Service, posted December 10, 2019. https://www.episcopalnewsservice.org/2019/12/10/baptizing-child-of-early-enslaved-africans-helped-tie-episcopal-church-to-slaverys-legacy/.

1820 U.S. Federal Census, record for Joseph P. Minnick, Gallatin, Sumner County, Tennessee

1830 U.S. Federal Census, record for Jos. P. Minick, Davidson County, Tennessee.

1840 U.S. Federal Census, record for John Shelby, Davidson County, Tennessee.

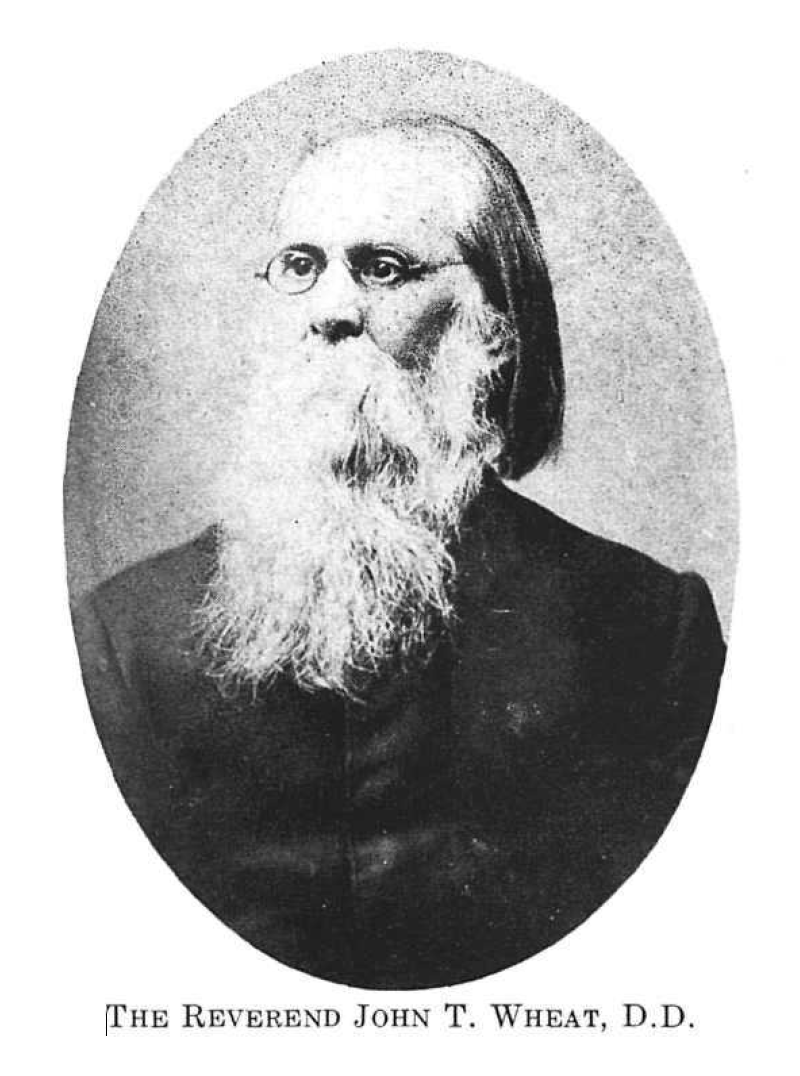

Rev. John Thomas Wheat performed Christ Church’s first known baptism of a person of color in 1841. Source: Anne Rankin, ed., Christ Church Nashville, 1829-1929, Nashville: Marshall & Bruce, 1929, facing p. 81.

Christ Church parish register showing the baptism of Mary Jane on March 5, 1841. Source: Parish Register #1 (1827-1848), p. 206. Christ Church Cathedral Archive, Nashville, Tennessee.

Tomb of Joseph P. Minnick (d. 1835), Christ Church founding member, slaveholder, and former enslaver of Mary Jane who was baptized by the Christ Church rector in 1841. The location of Mary Jane’s grave is unknown. Source: Joseph P. Minnick - tombstone inscriptions. Nashville City Cemetery Association. https://thenashvillecitycemetery.org/280151_minnick.